The passion for wood and drawing that turned real

The passion for wood and drawing that turned real

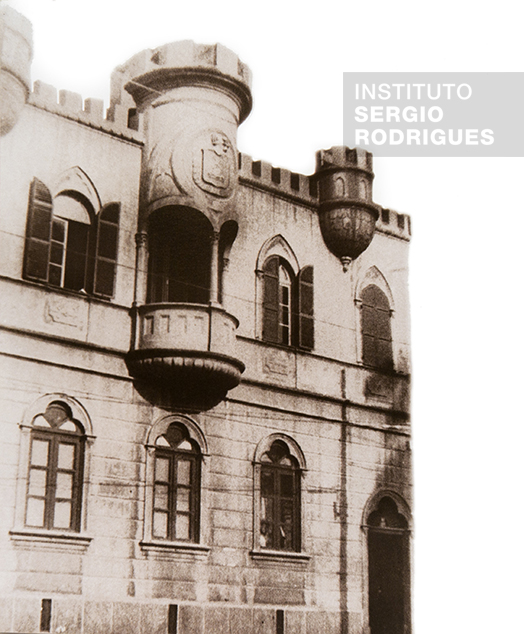

The house was shaped like a little castle and everyone called it “72,” its number on Flamengo Beach. The little castle belonged to James Andrew, whose sister was married to Fernando Mendes de Almeida, Stella’s father. Uncle James had a huge influence on Sergio’s upbringing. Passionate for furniture and wood, James had a carpentry shop in the back of the farm that surrounded the house. The backyard went all the way from Flamengo Beach to Catete. In the back it had a huge orchard “with incredible fruit,” several types of mangoes, a lot of room to play soccer and run in at will. While describing the “72,” Sergio’s voice rejoiced and his eyes sparkled with the fun, vivid memories he had of the place:

“I didn’t need to go out on the street to have fun. I used to take friends home, played soccer and was always having fun. There was a soccer field there, and I learned how to barbecue. Berries, mangoes, jambul, avocados, bananas, all of that on the other side of the gate. There was a part of the yard where there was a large iron door leading to the farm where the fruit trees were. The little castle’s facade featured the family shield, which had a deer in it. My uncle did nothing, he was rich. A National Guard colonel, he had been an adjutant of Marshal Hermes. Woodwork was his hobby. The basement of the house was full of the remains of old houses that he gathered. There was furniture and fixtures, it was great. Amazing things. And we, children, were libertarians; we used to make a big huge mess.”

“At the little castle, in the mess basement, there was a lot of old stuff, old chandeliers, and many other things. It was below street level, and when there was a storm tide, water would splash into the basement. He had his woodwork shop in another room, in the backyard. The bottom part was his joinery, on the top were the employees, and I had my mess studio in the last room. The chicken coop was next to it.”

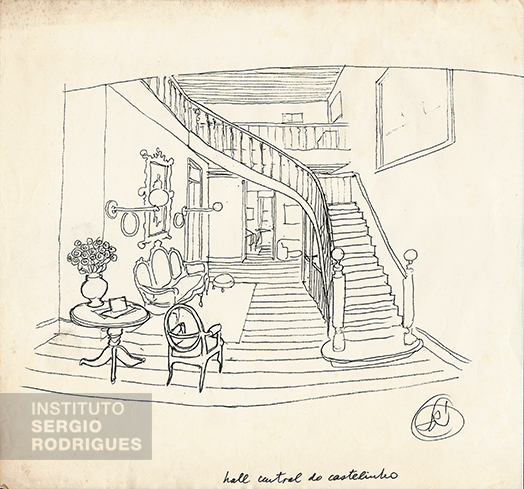

“In the mess basement there was a ladder leading up to the house. It was all crafted in wood, made by uncle James. He also liked to invent and manufacture chairs. One of his habits was having two colors of wood: light and dark, peroba and Jacaranda. Everything was done that way. Dark and light wood wainscoting covered the full length of the dining room. It went up a meter and a half and went up to the middle of the wall. He would order his carpenters to do the work and would stick his nose in everything they did. They were excellent. In order for his woodworkers to understand what he wanted, he would make drawings to show them what he was looking for. He would use foolscap paper and red ink, with a feather that fit into the pen. The drawings were horrendous, no one could decipher them, but the Portuguese woodworkers understood what he wanted.”

Although he was very young and all the time he spent at “72” was an intense experience in fun and games, the way his uncle communicated his ideas to the woodworkers through drawings was the key for Sergio to start drawing and end up heading into architecture and design. “It was the great click,” he said. Realizing that things could be made from drawings, designs, was a revolution, even if unconscious one, in the boy’s mind, because humor and imagination were already flying around free in Sergio’s childhood.

The uncle’s workshop was the old stable there used to be in the back of the house. The stable was later torn down and the wood was all used. Sergio used the leftovers to make toys and play games. “I thought I could play around with the wood too. It would be easy because instead of using dough, all you had to do was to make it out of wood. We used to make a lot of things out of dough, especially wax, such as toys. We used church wax, the one that accumulated next to those candlesticks that spill wax. We would shape it. I then wanted to use the woodwork shop there was at home. There are a lot of small cedar boxes that I used to make toys and that was, incidentally, one of the types of wood I used a lot because of its smell. The smell of cedar, the smell of a box of cigars, it was all very exciting to me.”

The playful mood of his childhood surfaced later on, and often, in his work. “Sergio sees furniture like toys. The Burton table, for example, has both aeronautical and naval elements. It looks like he took a few parts of a sailboat to make the table. But he does not mess around. This table has a rod that is not there as a mere ornament. If you remove it, the table will not stand firmly. It has plastic beauty and a structural function both.” It is Fernando Mendes de Almeida, a friend, cousin and pupil, who says so.

Sergio continues talking about the enchanted world he lived in as a child: “Aunt Léa’s home was next door, and there was a sapodilla tree there. The bats used to eat its fruit, but it was the best. I used to do all kinds of things at uncle James’: I even built a lift to get the dog up on the sapodilla. Fly was my dog. I would pull her up, and she would stay up there with me. There was the pantry and the service staircase leading to the pantry. I used to like to make milkshakes, but since I didn’t have the tools to make them, I would take milk and coffee up those stairs and spill it into a cup in the pantry from up there. That would make foam and I would drink it as if it were a milkshake. Mom would spank me. Then, when she got tired, she would order me to go get a belt to be spanked with. I used to pick the most beautiful one.”

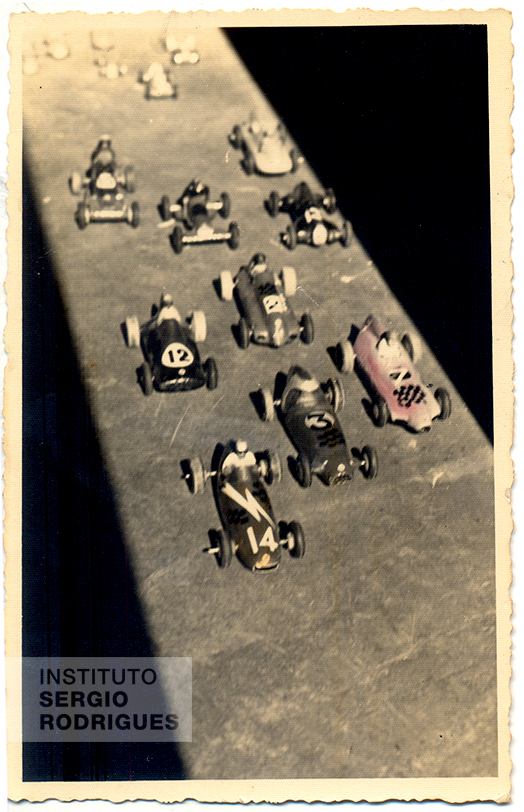

It was a huge mess, and the entire house seemed to invite the most creative and daring games. The taste for speed and the car craze were still there: “There was a bathroom in the manor from the Dom João days. There was that large tub with small feet on it. And there was a tool to heat the water. It was a strange object. I used to pick it up in a certain way and played a dangerous game with it: I would somehow push the water away before starting the machine. The thing would explode and the lid would fly down there. It always happened at bath time, and Grandma would come running. Next to the house there was also the Astoria hotel, with rooms facing our inner courtyard. Employees and customers used to complain all the time. To make even more noise, we built a scooter using ball bearings. So it would seem like a car race, we used to put zinc sheets on the ground and race on top of it all.”

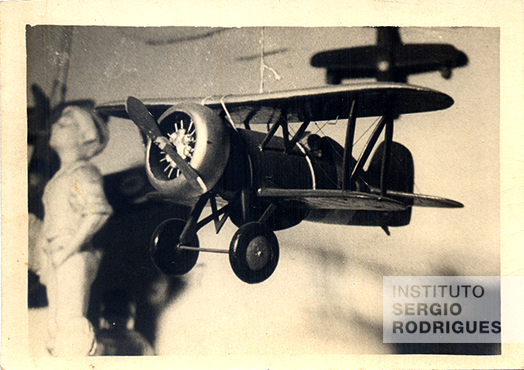

Sergio loved making his own toys. From his childhood inventions came many ideas and experiences that he absorbed and used later on in his creations. He devoted himself mainly to his favorite toys, which he built by intuition. Aircraft wings were one of his passions. “I would take the side of a box, which was practically a wing. All I had to do was sand it down. To make the plane’s fuselage – it was always a biplane – I would make a tiny, thin body and then put on either side and glue it. I later started using hardboard.” He also used to build sailboats, another one of his great passions. He was not interested in motorboats, speed boats or ships. It was sailboats that made him imagine drawings of super aerodynamic parts that could be made. With nowhere to try his boats out, other than occasionally at an aunt’s place where there was a pond, Sergio often sailed them in the Guanabara Bay. “We lived right there at Flamengo Beach, on the seafront, and there was a ramp to the Flamengo Club. I used to take those tiny boats there and let them go. I would just sit there and watch them go.”

Later, he started to build balsa wood aircraft with screens and Japanese paper. And, after a while, he would throw the plane from the window of his house. “It was a big two-story house. I would throw it from up there and it would fly.” But his imagination never settled down. “Some time later, I decided to experiment with wrecks. I would soak a piece of cotton with a little alcohol, light it up and hurl the plane. And I would watch it go down in flames, a big disaster.”

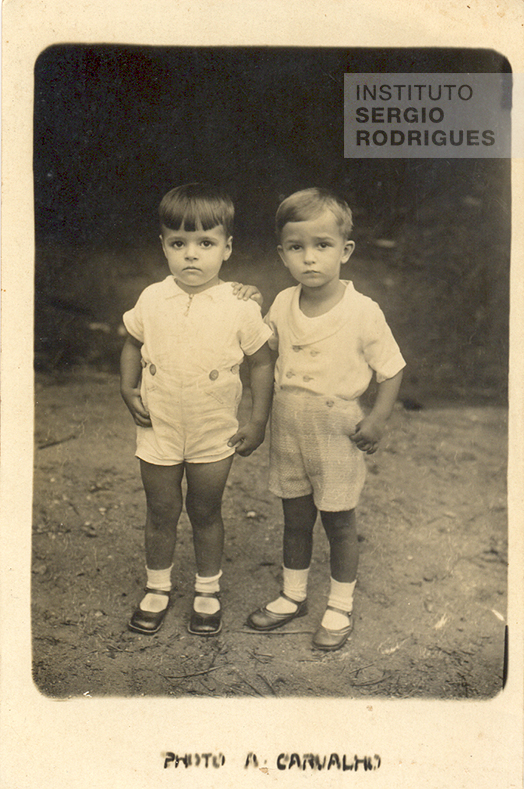

It was not just airplanes and boats. There was imagination for everything. “We had an imitation radio. It was a metal soap dish. Friends, among whom Candido Mendes, used to go over to my place to sing on the radio: we used to call it the General Tranquility Grinder Radio. I used to scandalize the neighborhood. I got spanked a lot. There was Eduardo, who was the son of the maid and four years older than I was. He helped me a lot making huge messes. Eduardo and I once built an airplane. He had good ideas.”

The passion for interior decoration came from many places. One was by analyzing the furniture of the houses where he lived. “All the furniture in my house was deco. Nearly everything was deco. Even the chandeliers, everything.” Later, Sergio realized that his father, Roberto, was the missing link between art deco and the expressionist modernism of his drawings and of those of his famous friends.

Another source of his passion came, of course, from grandmother Stella’s hat “factory.” Stella had a sewing room on the second floor of his uncle James’ house. She designed and sewed hats for her chic Rio de Janeiro society clientèle. To showcase and try the hats, she had a female bust made out of papier-mâché. And there were mannequins around the house that Sergio and his sisters loved to use to scare the maids. They used to dress the mannequins up, put the papier-mâché head on them and position the spooky piece somewhere in the dark.

His talent for lines also came from his family. “Grandma used to draw figures that I really liked. Mom also drew.” And, despite his brief life, his father was considered a drawing genius. Sergio grew in this creative atmosphere, and everyone admired his drawings and games.

“They used to think I was a genius. Mom respected my games a lot. I used to paint the walls of my room with amazing Machiavellian figures. Mom would not get mad. Instead, she would tell people not to go in there because I was painting. I keep a story for psychoanalysis purposes: I painted a candlestick with melted candle wax that looked like breasts. I had no malice at all. But Mom came and said: ‘What is this? You doing indecent things like this?’ It was hard back then. My maternal grandmother forbade me from putting my hand in my pockets, and you could not sleep on your stomach.”

After she married Dadi, Elsa and her husband built a house in Gávea. They ended up moving there with the girls. Sergio stayed at uncle James’ with his grandmother because it was much closer to school. He lived at “72” until 1949, when uncle James died. Sergio was 21 at the time. Uncle James left the home to Stella, but she, unable to support the little castle, sold the property. The grandmother Sergio loved so much died ten years later, in 1959.

Main façade of Castelinho, at Praia do Flamengo, No. 72 - Rio de Janeiro, around the 1920s, where Sergio lived with his mother, Elsa Maria, and uncle, James Andrews, from childhood, in the 1930s, to age 23.

Little dragon carved from cedar that decorated the main mirror belonging to the Castelinho living room at Praia do Flamengo, No. 72 - Rio de Janeiro.

Drawing Sergio Rodrigues made from memory representing the skylight hall at Castelinho. at Praia do Flamengo, No. 72 - Rio de Janeiro.

From left to right, Sergio Rodrigues, at age five, next to his cousin Cândido Mendes, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1933.

Sergio Rodrigues' model car collection, one of his great childhood passions.

Solid cedar model aircraft made by Sergio Rodrigues at his uncle James Andrew's workshop, at Castelinho, at Praia do Flamengo, No. 72 - Rio de Janeiro, in the 1940s.