The industrial experience with semi-artisanal furniture

The industrial experience with semi-artisanal furniture

At first, as has been said, 95 percent of the furniture Oca sold came from São Paulo (from stores such as Forma and Ambiente). The remaining 5% were Sergio’s drawings: the roundish stool (Mocho), small sofas, coffee tables. But Sergio wanted a store that could meet the needs of a broad audience. “I was kind of disappointed because since it was not industrialized (although it could be), my furniture came out of the oven with a very high price tag.” He also noted that the workshops that were making these prototypes went on to incorporate them in their lines. Furthermore, there was increasing demand for furniture. To solve this issue, Sergio started thinking about opening a factory.

Thus came Sergio’s first plant in Rio de Janeiro, in 1956. The small factory was named Taba, and was in Bonsucesso. Although the idea was to manufacture on an industrial scale, Taba still made its products by hand. “Thus, the quality of the raw material did not influence the final cost very much, and Jacaranda was rehabilitated, putting an end to the supremacy of pau-marfim.” Rio de Janeiro joined the map of modern Brazilian furniture. Three years after Oca was created, Sergio no longer imported furniture from São Paulo: 100 percent of the models were his creations. In 1958, they were cited internationally by Gio Ponti in his Domus.

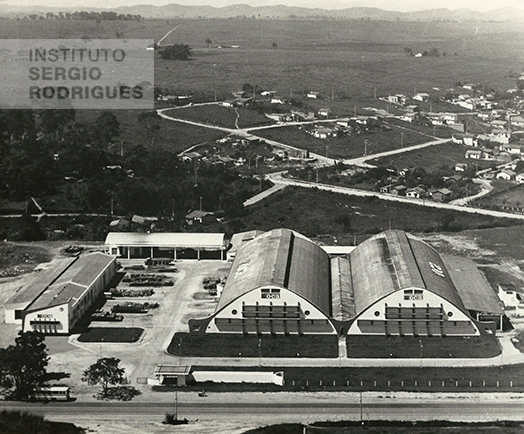

The industrial experience was a challenge for Sergio. At first, three or four models of furniture were manufactured at a time. But there was a surge in demand, and it became necessary to make a larger series. Years later, still at Oca, Sergio opened another factory, this one much bigger, with 10,000 square meters of covered area, in Jacareí, state of São Paulo, which he called Oca.

Oca Gallery

Oca launched furniture. And artists. For those events, it also became known as Oca Gallery. Among many others, Sergio introduced the painter, sculptor and printmaker Juarez Machado, who had come from Paraná and became famous shortly thereafter. The architect Dolly Michailovsky, who worked with Sergio at Oca for many years, emphasizes what many already knew about Sergio’s personality: “Sergio was incredibly open. Everyone who had something to do with Sergio became great friends of his. He always valued what we did. Being around him was a human experience, and a life experience. As a creator he was amazing. An unbelievable talent. It was something that sprang right out of him. There was not much of a working method, he was loose, an artist. He drew all the time.”

Dolly studied architecture and had a boyfriend who lived near Oca. Her interest in interiors surfaced because of Oca. One day, a recent graduate took courage and climbed the stairs that stood in front of the store’s entrance door and went talk to Sergio, who spent nearly all his time working in this room, upstairs from the store. She could hardly believe it when Sergio listened to her attentively and invited her to work there. “He gave people a lot of space. I helped design and present Sergio’s projects.” When she got married, Sergio gave her a Mole armchair. “Sergio is unforgettable. Anyone who knew or worked with him knows that.”

At that time, Sergio made scenarios for the plays of the theater located next to the store. And other ones, such as for a play at the Copacabana Palace, by Peter Bloch. In that same period, he decorated singer Roberto Carlos’ home with Oca furniture. Roberto called him “prafrentex” (very modern), but Sergio said he was nothing of the sort. The house was decorated, at the time, with all of Oca’s furniture and looked more like an exhibit of the things there were in the store.

The researcher Maria Cecilia Loschiavo dos Santos, who has written several books on modern Brazilian furniture, says “Sergio Rodrigues created objects whose forms are very present in the Brazilian collective imagination, close to the land, to the hammock, to the cot, to the way the hillbilly, the gunman, and the backwoodsman sit, to the simple indigenous object, the work of these two artisans who made the cross in the beginning of Brazilian history, in 1500.”

The “Meia-Pataca”

Sergio was bored because he wanted to create new things, design new furniture, not just sell things that were already known. “I used to get very upset because I am not a trader by any means. I was bothered by having to sell furniture and make other pieces. My partner used to say: ‘You sell Oca furniture. You may even invent other things, but you have to sell Oca furniture.’ And I used to do that whole thing, pushing Oca furniture… but I always wanted to do something new.”

Oca furniture started being purchased by government offices, banks, institutions. They all bought back then. At that time, Brazil’s new capital was being completed in a hurry, and Sergio was recruited for many projects in Brasilia. That was when mass consumption started surfacing in this area and Sergio, who at first had his work focused on providing solutions for modern architecture, for public buildings spaces, and started getting orders from private customers.

But Sergio was not satisfied yet. He wanted a larger audience to be able to buy his furniture. In the meantime, in order to sell furniture made in series at lower prices, in 1963 he decided to establish the Meia-Pataca shop, which remained on the market until 1968. It was a buying alternative for the middle class, because at Oca his furniture ended up being targeted at a high-income market. In addition to furniture manufactured in series, Meia-Pataca also started selling products that were simpler to implement and, therefore, more accessible. He set a limited number of products and decided to use a different type of wood at Meia-Pataca, other than Jacaranda, which was used at Oca. He went on to use Gonçalo Alves wood (today called Maracatiara or Muiracatiara in São Paulo).

Meanwhile, Sergio associated himself with two Americans, enthusiastic about his furniture, and with them opened, between 1966 and 1968, a store in Carmel, United States, which he called Brazilian Interiors and permanently showcased models he had created. His furniture was a unique attraction. Sergio loved it. “It was a very friendly shop located in a shopping mall made entirely out of wood.” The California store proved that Americans, even then, liked Sergio ‘s furniture. “I think it was such a great hit because the entire West Coast was created by Latinos, and they had no current furniture and could get no designer to do this kind of work. When they saw my furniture they were very excited. The store sold my furniture exclusively for two years.”

The end of Oca to Sergio

Oca was moving ahead at full steam, but business not so much. Sergio did not participate in the store’s management, and although it was a hit, business was not going well.

For Sergio’s misfortune, because he never had eyes to other people’s wickedness, another partner that was in business with him from the start proved to be poor manager and eventually led Sergio to bankruptcy. Friends and family were trying to alert him of how poorly business was being conducted. Naively, Sergio did not believe them. Therefore, his business skills did not keep pace with his immense creative capacity. When the Italian partner, Grasselli, realized that business was not going well administratively because of the third partner, he decided to leave.

With Grasselli’s departure, the store ran out of money. That was when they called Giulite Coutinho, who later, between 1980 and 1986, would be president of CBF, to be its venture capital partner. He immediately realized the store was poorly managed and fired Sergio’s partner, and Sergio, in solidarity, also left the store that he himself had created. The same year he left Oca, 1968, he also closed the Meia-Pataca.

Sergio was distressed. By now he had four children. Veronica, Adriana and Roberto had been born. He didn’t know what to do. A little later, he asked his former partner to give him his shares because Giulite wanted to buy them. Only then did he find out that they had evaporated into thin air. That is, they no longer existed. Feeling disappointed with his partner, Sergio apologized to Giulite and they were friends until the end, although Sergio never became a partner of Oca again. After thirteen years as a partner, from 1955 to 1968, Sergio resigned from Oca.

Shortly thereafter, Sergio set up a studio in Rio, where he worked with interior design for homes, offices, and hotels and undertook projects for various clients, including for the owner of the Bloch publisher, Adolfo Bloch, doing the entire interior of the publisher’s headquarters in Rio. He also developed furniture lines for industrial production. It was then that he participated in the “Brazilian Furniture – Assumptions and Reality” exhibition, at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP).

Sergio was already married to Beatriz Vera, an old childhood sweetheart, who fortunately took over the task of managing Sergio’s professional life. From then, his furniture went on to be made by contracted suppliers case-by-case and, in 2000, Gisele Schwartsburd, from Curitiba, signed a contract with Sergio, brokered by Vera, to open Lin Brasil, a company that would only make his pieces. Without production concerns, Sergio could return to give vent to his incredible creativity and went on to create projects incessantly, like a “think-tank”.

Aerial view of the Oca furniture factory, in Jacareí, São Paulo, in 1965.

Storefront of the Oca Furniture store, Carmel - California, United States, 1965.

Interior of the Oca Furniture Store, in Carmel - California, United States, dated between 1965 and 1968, when the store operated.

Cover of the Meia Pataca line catalog, 1968. Logo created by Goebbel Waine, in 1963.

Meia Pataca line catalog, 1968.