"If I could sum it all up in a single shot, design is creation." (Sergio Rodrigues)

“If I could sum it all up in a single shot, design is creation.” (Sergio Rodrigues)

Sergio always resented the fact that nobody ever gave him a good explanation of what design was while he was in college. There was not a practice of showing and remarking on the design of a chair, an armchair, a sofa, or any object. So, intuition was always a strong vein in Sergio’s training. After all his experience and background, Sergio could theorize about design and create his own definition, as he did in conversations he had with art critic Afonso Luz:

“Design is an element that, added to technique, is a mode of work in which you add something to things. Whether aesthetic, technological, design adds something to the object. This addition is what makes a difference, an impression, and it is also what causes an issue to people who do not understand design. Because they always imagine that design is related to the product’s aesthetic appearance, it is the plastic part. But in reality, design is a series of elements, among which the drawing and beauty it adds to the product’s appearance, that give the product a few visual predicates. If I could sum it all up in a single shot, design is creation. To me, everything related to creating is design. Everything that is created is design.”

As he developed his theory during his career, Sergio was also learning what design was in practice. He had to work this characteristic in his daily realization, mainly when coming to grips that design is closely linked to trade. One of the characteristics of design, he said, is to provide economic benefits to those who consume it, or also cultural details, which are very important for one to appreciate the work, to differentiate one product from another in the customer’s eyes. “It is in the way these things are applied in the study of a design that you value the work.”

Nevertheless, Sergio said he was not called a designer. “If you ask me what I am, I say I am a furniture draftsman.” To him, design is a part of the construction profession. As architecture should be. With humor, he accurately explained the function of good design. “Architecture students should spend some time in a wood workshop. Do it in practice. Use construction techniques, not only with wood, but also with iron, concrete, etc., in order not to do something stupid. Because designers often imagine many wonderful things and sometimes they do not work. That is the case of this little object that is cute as hell, this thing that I gave myself, which is a thermos, it attracted me a lot at the time. I bought it real fast. I took it home, and when I got there the thing did not work. Why? You would put coffee in there… And to get the coffee out it, how did the thing work? What do you do? You have to press down on it. After a long time, then you press on it. By then you had a big mess on the table, on the floor…”

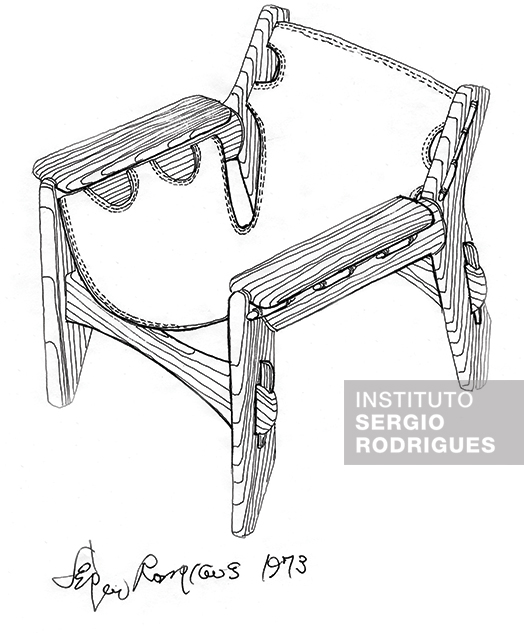

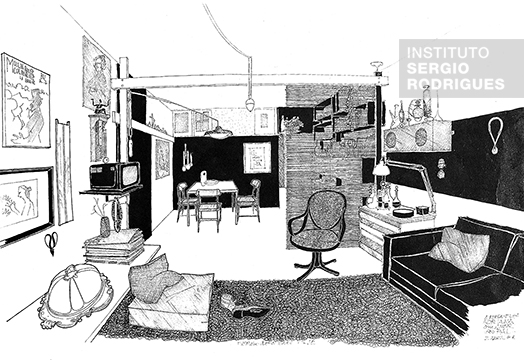

Sergio used to say that his most important testimonial was his daily work. His drawing was already a construction. His capacity for synthesis in projects always drew attention. He could even design a large table on one or two sheets of A4 paper, in scale, with details and life-size cuts, without repeating or leaving information out. “It’s all there, complete,” explains Fernando Mendes de Almeida, who worked nearby Sergio for many years. “He said he was bad in math, but was excellent in geometry. In furniture design, especially of chairs and seats, you make the blueprint, the cut and views, everything overlapping and in one design.”

What Fernando admired most in Sergio was his ability to draw, but also the freedom he allowed himself in the drawing. “He is free in his creation. His things have a huge playful appeal.” And he joked: “I think he makes toys, not furniture. In some pieces, when manufacturing them, you can see the toy being born. You assemble it all, using a lot of aesthetic resources on different pieces, but it is all a game you put together. Some things seem very simple, but sometimes they are complicated to manufacture. Others seem super complicated, but production is quite simple. He plays with these things. And he always knew how to create according to the technical resources available for manufacturing.”

The power of synthesis in Sergio designs has the advantage of simplifying the understanding of the design, preventing the manufacturer from getting lost, since objectively guides the construction of the piece. “He brings all the alignments, the rotation of the plan. This type of design clearly conveys the feeling of the object’s volume. You see the thickness of the wood, how the pieces match, the exact size of the fitting, especially when there are curves. It is all there, all the information to make the part in its actual size in all three dimensions. His design is already half way to making the piece itself,” assures Fernando.

One of the strongest memories in Sergio’s childhood, which paved the way to design, was to see uncle James designing furniture, delivering it to the carpenters and, from there, a product actually being made. This idea that design eventually becomes something tangible, manufactured, awakened his vocation.

Fernando learned a lot by watching Sergio draw, observing him working. Today, people design their projects on the computer and in 3D and you lose the direct relationship there was in the past, like Sergio had with his pencil, paper and line, which is imperfect but brings the warmth of handmade design. You lose your intuition.

“The pencil’s texture on the paper is warm, a part of a construction, it brings a wealth of details, information, emotions. I learned a lot with him. Sergio worked as if he were in pursuit of a treasure which, at a given moment, he indeed found. As if something was outside of him and another inside and suddenly this marriage happens. Then you arrive at the drawing and realize: ‘That is what I wanted.'”

Sergio never designed on the computer, always freehand, even technical drawings. Sometimes someone drew for him, but under his supervision. He used to make a draft, he would not get lost in minutiae. It was loose, free. He had stopped making large drawings some time before, but drew on small pieces of paper, on a scale and with details in natural size. Veronica, his daughter, also chiseled away extensively on her designs.

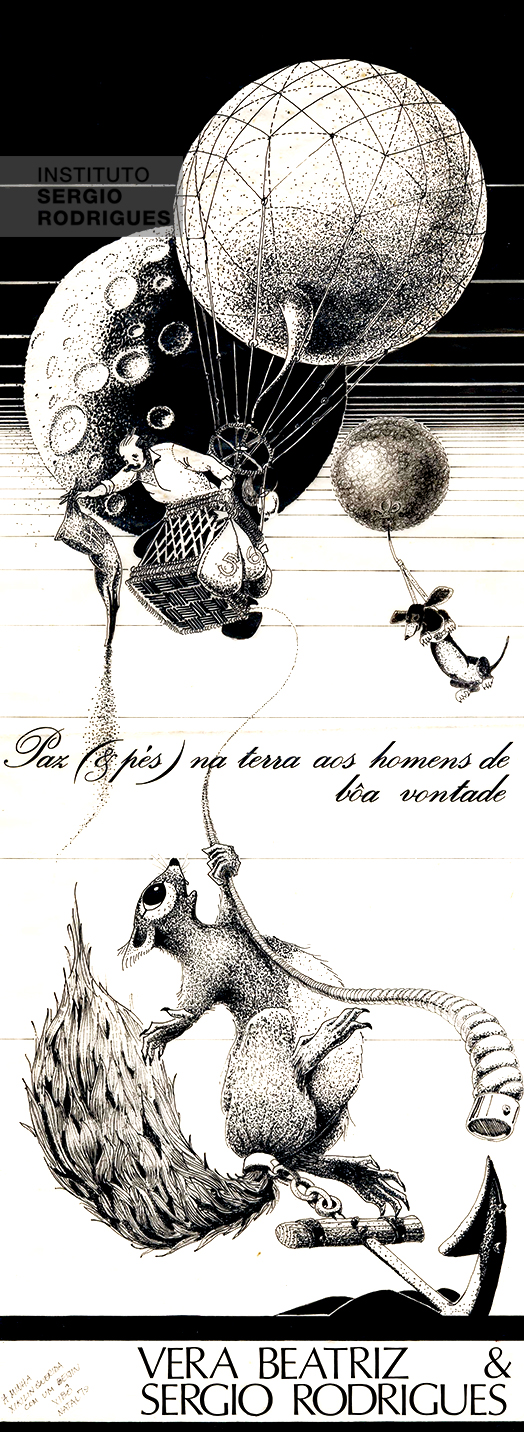

The illustrator and designer

Sergio did not stand out in project design alone. Like his father, Roberto, who had a short, productive life, Sergio was also an accomplished designer. “I like Sergio’s verve, in everything he does, even in his design,” said designer Freddy van Camp, also a former collaborator and admirer. “His design has a lot of humor in it, and I think he would have had a career as a designer if he had not dedicated himself to architecture and furniture design,” said journalist Adélia Borges.

Sergio used to make drafts and often threw out his drawings until he got where he wanted. Fernando was around Sergio in many moments of creation. “I once saw him drawing a table. He drew, drew, and made those typical holes with his circle template. And he said: ‘It took me a long time to find the right place for this ball, but now I have found it’ – and it is just perfect this way, he joked. One day he was at his office, tired: ‘There’s no point to sticking around here scribbling if I have no good ideas in my head. You need to wait for that kindle that will guide your work’.”

Sergio made drawings and caricatures his entire life. Many drawings were dedicated to Vera Beatriz. He did it rather as a kind of seduction to her. The drawings of Vera Beatriz tell his stories. And often they were fun self-portraits. One day he was in an old clunker and she in a flying saucer. Or he would be in a caricature, sprawled on a Mole armchair. The drawings always had stories. And there were also the freehand drawings showing details of a part or the straps of the Mole chair, the first ideas. He drew a lot next to Vera Beatriz. In many of the drawings he is a rat and Vera a squirrel. In fact, as we know, that is where the Kilin armchair’s name came from – Vera Beatriz’s “little squirrel” (“esquilinha,” or “kilin”) nickname.

Sergio’s mood shined through even in his architectural work. He always did something funny in his projects, an illustration here, another there, that represented life in that home or office. He once designed a house in Angra dos Reis for Antonia, the daughter of Kati Almeida Braga, with a deck in front of the house and the pool built into the deck. In perspective there was a woman inside the room wearing a bikini. And another one in the pool, turning around in the water.

There are many examples. Another time, he drafted a design for a military man and added an old boot with a hole in its sole next to the couch in the drawing of the setting. The man was offended by that and Sergio lost the project because of the joke. On another occasion, a customer asked him to draw a lake on the grounds of a farm in Itaipava. He wanted to have a space to welcome his guests lakeside. Sergio and Veronica imagined an archaeological house that had already been on the grounds for centuries. Sergio drew two huge, robust pillars, as elements of an ancestral home. However, the project also included a contemporary feature, as it had a deck leading to the lake floating between these pillars. And the final, humorous touch was that he added a gondola drifting by in the drawing of the lake.

Sketch of the Leve Kilin armchair made out of solid hardwood and leather, black canvas or "atanato," created by Sergio Rodrigues in 1973 in tribute to Vera Beatriz, his wife.

Illustration by Sergio Rodrigues about a trip to New York with Kilin – Character idealized by Sergio to represent his wife Vera Beatriz – and daughter Verônica Rodrigues.

Drawing by Sergio Rodrigues of his apartment at Rua Visconde de Pirajá, in 1956, created for the article titled "The Mirror of the little dragon," published in Senhor magazine in 1963.

Christmas card created by Sergio Rodrigues, in 1979, in honor of his wife Vera Beatriz.