Sergio Rodrigues started presenting his work in a context that was already teaming with the idea of modernity and was daring to take the first steps in Brazilianness

Sergio Rodrigues started presenting his work in a context that was already teaming with the idea of modernity and was daring to take the first steps in Brazilianness

When Sergio Rodrigues graduated from the college of Architecture, in 1952, the winds of a new modernist language coming mainly from a Europe interested in “rationalizing” domestic life started blowing in Brazil. The Industrial Revolution had changed hearts and minds during the eighteenth century and laid the foundations of a more practical, less artisanal and sophisticated life. With the end of the two world wars, Europe found herself immersed in movements that were reviewing the wasteful life of the elites before the conflicts and betting on a more rational, economical life.

In Brazil, the higher classes were still dazzled with European furniture, upholstery made of velvet and other fine fabrics, which hid its internal design, such as the French furniture that Sergio called “ladies” furniture, “full of embellishments”. The designer and sculptor Joaquim Tenreiro, creator of iconic Brazilian furniture, used to speak of the style “of all Louises,” referring to the kings of France. But even in Europe, this type of furniture was still what people wanted.

The European rationalist movement then began to move away from that style, which marked the taste of the wealthy homes of that era. In the early 1910s, a line of thought that introduced new proposals that preached “the shape that follows the object’s function, and function alone” surfaced in design.

When Sergio became interested in creating furniture in the 1950s, attempts to make the modern Brazilian furniture were already emerging in the country. In the 1920s, for example, Gregori Warchavchik, a Ukrainian architect and designer who had studied in Italy, immigrated to Brazil and built the first modernist houses in the country. He used to support the rationalist furniture idea, already in vogue in Europe, and launched the first modernist architecture manifesto in Brazil. He introduced the metals that were widely used in the European rationalist language to his furniture, but did not absorb Brazilian influences or the materials found here. On the other hand, he focused on designing the purer lines of the modern language and joined a group that also included Lasar Segal, a Lithuanian painter and sculptor who moved to Brazil in 1923 and also ventured into furniture design.

Warchavchik dreamed of manufacturing furniture in the industrial reproduction series, but it was not yet time for that. Society was used to references coming from other times and places, and was not ready to accept the new modern furniture, so his dream did not come true in his time. Nonetheless, those were the first steps taken towards a new furniture design, although not on the path towards a Brazilian project.

Change was on its way, though. In the transition from artisanal to industrial furniture, around 1906, the Gelli furniture factory, a brand that exists yet today, appeared in Petrópolis. However, to the Brazilian journalist and design expert Adélia Borges, the great watershed separating artisanal and industrial furniture was the Patente furniture factory, established in 1910. Essentially, Patente manufactured popular furniture, although a few of its pieces were more refined.

Soon thereafter, in 1913, the Cimo furniture factory was inaugurated in Santa Catarina, a pioneer in designing products that could be taken apart and were ready for industrial scale production. There was so much demand for Cimo’s furniture that the federal government department in charge of procurement at the time imposed Cimo’s measurements as the official standard measurements, thus giving rise new impetus to the factory’s production. Government offices, cinemas, and schools used Cimo furniture and, in 1941, more than 500,000 Cimo armchairs had been installed in concert halls nationwide. The factory then became the largest furniture plant in South America.

Meanwhile, an event in Germany would reinforce the avant-garde wave of furniture design throughout the world: In April 1919, Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus school of design, art and architecture, supported largely by the Weimar Republic, which remained in place until 1933, when it was closed down by the Hitler administration on account of its leftist orientations. Bauhaus influenced one of Brazil’s main architects, Oscar Niemeyer, who designed Brasilia based on the modern and functionalist tendencies of the Bauhaus school.

In this innovation-filled environment on the international scene, where the idea was to break away from the ornament and the notion of stylistic embellishments, appeared Dutchman Gerrit Rietveld, who radicalized and proposed furniture construction be very well explained. He removed all skin and layers from furniture, leaving it like a skeleton. With colors, he depicted these components and created the famous Red Blue chair in 1932.

Pushed by the same daring spirit came Le Corbusier, a Swiss architect, designer, and painter who traveled to South America in the late 1920s and stated that “the house is a machine to live in.” Along with the Brazilian architect Lucio Costa, he would be in charge of the project that became a landmark of modern architecture in Brazil: The MEC (Ministry of Education and Culture) building, in Rio de Janeiro, built pursuant to the modern architecture with the Brazilian temperament.

In the wake of the international rational movement came Mies van der Rohe, a German-born American architect, professor at Bauhaus, a follower of a style that left the mark of a rationalist, geometric architecture who proclaimed: “Less is more!”. The American architect Louis Sullivan, who had been around longer and was considered the father of modernism in architecture and the “father of skyscrapers,” the mentor of Frank Lloyd Wright, once again set the direction to be followed by the modern design and architecture which became the motto of Bauhaus: “Form follows function.”

In 1952, nearly twenty years after the closure of Bauhaus, and to promote its principles, Max Bill created the Ulm School of Design in Germany, also known as Superior School of Form, which closed in 1968 for political and financial reasons. The school brought together architects, designers, filmmakers, painters, musicians and scientists, among others, and was meant to train professionals with solid artistic and technical foundations for creating objects produced on an industrial scale for everyday or scientific use. The Ulm model resumed the relations between art and crafts, art and industry, art and everyday life.

From these “thinkers” of the new aesthetics of architecture and design came a European furniture trend created pursuant to the thesis of the “maximum expression with minimal elements.” This is the uncluttered furniture, as opposed to the stylish one. When, in 1928, Warchavchik designed the first Brazilian modernist house, in São Paulo, he wanted to create a kind of rational, comfortable, purely useful house. A good machine to live in, with simplistic lines and compatible with mechanized requirements. But there was no talk of Brazilianness because the rational furniture was independent of time and place and it was an avant-garde European trend.

An example of the new thinking was the Wassily chair, designed by Marcel Breuer, an American architect of Hungarian descent and professor at Bauhaus, who broke away from paradigms by introducing new materials like tubular steel and by using uncluttered geometric shapes.

This ebullience arrives in Brazil. “The Brazilian modernist movement,” says Adélia Borges, “has a clear influence on architecture and design. It preaches integration among architecture, furniture, and landscaping. Thus, architects went on to design not only buildings, but furniture, lamps and household items.” Together in the modernist movement were Warchavchik, Lasar Segal, and John Graz, a Swiss painter, illustrator, designer and sculptor, who came here, became an interior designer and was largely responsible for introducing art deco in Brazil. The painter Flavio de Carvalho, also an architect and designer, was part of the group and devoted himself for some time to designing clothes, adopting the modernist “Flavio de Carvalho uncovers Brazilian fashion from head to toe” motto.

Meanwhile, Oscar Niemeyer starts making the modern Cataguazes houses, in Minas Gerais, and invites Tenreiro to work with him. By making intensive use of Brazilian woods, Tenreiro spurred the creation of Brazilian furniture. At the same time, in the 1940s, the architect Lina Bo Bardi arrived in Brazil, coming from Italy, and was surprised she did not find modern furniture for her projects here. She then started to create furniture for her own projects.

As Lina, Zanine Caldas, who in addition to being an architect was also a landscaper, sculptor, and furniture maker, known as the master of wood, also started making furniture for his projects and even opened a furniture factory in São Paulo. The two produced a lot, but their furniture design was always subordinate to the architectural projects. Their design product factories did not last long.

Sergio Rodrigues started presenting his work in a context that was already teeming with the idea of modernity and dared to take the first steps in Brazilianness with Tenreiro’s projects. Already with an industrialization background and the new fresh air of the modernist language, he plunged into the mission of creating the Brazilian furniture. Architecture was a safe house for a while, and he lived off of it. As Lina and Zanine, he started designing furniture in the shadow of his architectural projects. Over time, design went on to gain autonomy in Sergio’s work. He began creating furniture that was not necessarily linked to an architectural project.

Sergio and Tenreiro developed their careers in parallel. The difference is that Sergio produced what he created. He opened a factory and started making his products on a large scale. Oca, which he created and became an icon in the 1960s, was a store that remained open for business for many years. In addition to it, there was Taba, Oca’s factory, on a large scale. Finally, with Sergio Rodrigues, design gained space on the Brazilian track of inventions.

(Adélia Borges collaborated with this chapter)

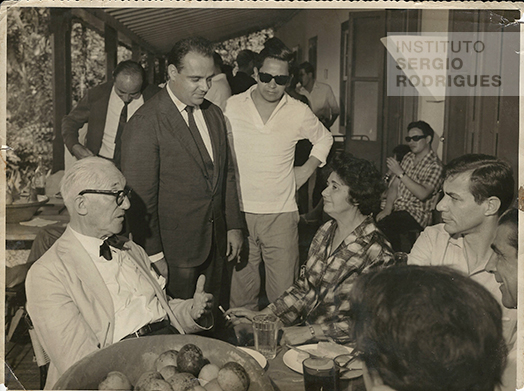

From left to right, Le Corbusier, Sergio Rodrigues, Jayme Mauricio, Carmem Portinho, and Harry Laus, at the Santo Antonio da Bica Farm (Currently Roberto Burle Marx Farm), Estr. Roberto Burle Marx, No. 2019 - Barra de Guaratiba, Rio de Janeiro, 1962.

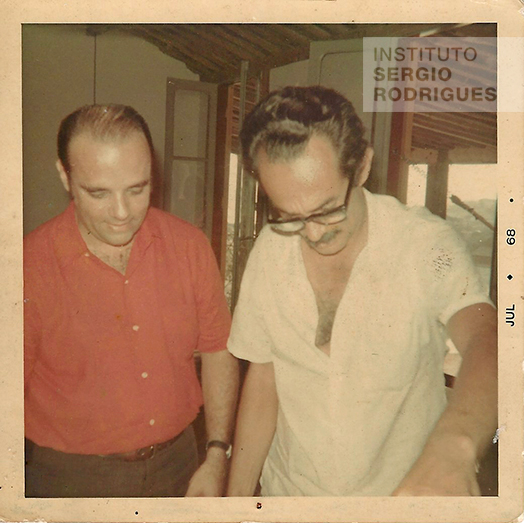

Sergio Rodrigues with Zanine Caldas, in Rio de Janeiro, in July 1968.

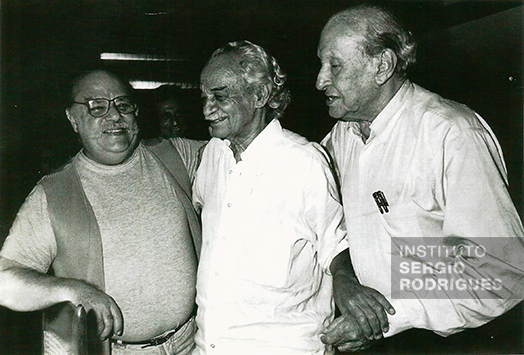

From left to right, Sergio Rodrigues, Vera Beatriz and Joaquim Tenreiro, Rio de Janeiro, in the 1980s.

From left to right, Sergio Rodrigues next to his friends Zanine Caldas and Sergio Bernardes, in the 1990s.

Sergio Rodrigues with his friend, the architect and designer Michel Arnoult, at a meeting in southern Brazil in the 2000s.