Sergio left us as he reached the top of his creative verve

Sergio left us as he reached the top of his creative verve

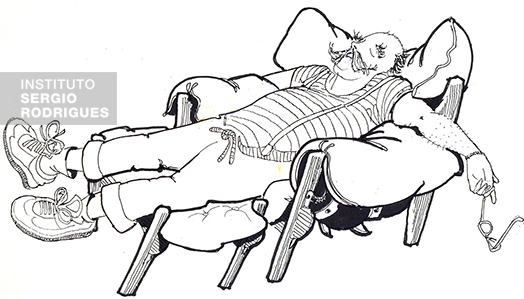

“May I have discovered the spirit of Brazilian furniture?” once asked the restless Sergio Rodrigues, after his Mole armchair was awarded. More than that, Sergio was able to translate the Brazilian soul into his furniture and to synthesize the way of being a “carioca,” as Rio de Janeiro natives are known. Easygoing, playful, an adept of informality, Sergio was always an open-hearted, unarmed boy. His mood contaminated his furniture and everyone around him.

“Until Sergio appeared, what ruled was furniture that forced people to sit with good manners and elegance. Sergio brought about complete informality and comfort. Mole embraces you, other pieces welcome you well and give you freedom to move,” said the journalist Adélia Borges.

Sergio left us as he reached the top of his creative verve. Were it not for the illness that took him early, while still creating and producing, we would yet today have the opportunity to experiment with his inventions, smart humor, and his passion for the craft he chose. As far back as the days of his store, Oca, in the 1950s and 1960s, master architect Lucio Costa was amazed at his dynamism: “Generous, instead of just celebrating his fabulous armchair, he remains active, he never stops.”

Sergio worked in many areas. He created 1,200 models of furniture. He designed pieces for offices, hotels, restaurants, gardens and homes, banks, and ministries. In Interior planning he designed settings, sets and created decoration, all in addition to his architectural work. He was the setting and decor editor for Senhor and Joia magazines, and wrote articles for numerous publications, including Módulo magazine.

He created for the Oca (from 1955 to 1968), Mobilínea (from 1961 to 1963), Meia-Pataca (from 1963 to 1968), Escala (1975) and Tenda Brasileira (1977) stores. In 1985, Sergio said that the trend in furniture would be to reduce it to the minimum and indispensable expression: Lightweight, practical, versatile, and inexpensive. One of his major contributions was to take interior design away from the realm of futile ideas and social status and put it within the field of culture.

When Sergio began, interior design was traditionally the stronghold of women, housewives, especially the richer ones who could decorate their homes. That was until Sergio went on to make a male professional contribution to an area dominated by amateur females. Men who were in architecture at that time cared very little about interiors. “Sergio was a male voice in the universe of interior decoration,” said Adélia Borges. “He is neither delicate or a mannerist. He is more incisive, rough, coarse, and this is not a negative evaluation. But that is his language. He gave up on the idea of the aesthetic beautification and embellishments.”

The researcher and critic Afonso Luz believes Sergio was able to approach a language of transition in international style, while he got a “modern Brazilian footprint that allowed him to create within it a full historical development.”

It was no coincidence that the international jury of the Cantu contest, in Italy, who granted his Mole the top prize, said that “(…) although it is not a copy or styling, this piece, created aiming at nothing other than to bring comfort and relaxation, blends indolence and Moorish sensuality that the fluffy cushions suggest, with the bravery of the people where crude leather represents protection against the harsh wilderness, nestled in a 17th century cot whose component robustness denote the plant wealth that characterizes a region, the North-Northeast, perspiring, unequivocally, the atmosphere of his home country, Brazil (…)”

Sergio’s biggest concern has always been with the human dimension of his creation. At a time when architecture predominated in the facade, Sergio thought about life “in there.” The furniture, he said, “is a key complement of architecture, pieces that define it, products that make up the architectural space in its interior.”

As is known, Sergio received many honors during his lifetime. In 1989, the whole of Sergio’s work was granted the Lapiz de Plata Award, at the Buenos Aires Architecture Biennial. In 1993, he participated in the Convegno Brasile – La Costruzione a Identita Culturale exhibit, in Brescia, Italy. In 2004, he was the subject of the Sultan in the Studio solo exhibition, at the R20th Century gallery, in New York, among other tributes.

Of the good memories he kept in his heart, during a 1985 interview granted to Casa e Jardim magazine he highlighted that he loved seeing the Mole chair as the only non-Scandinavian piece at Illums Bolighus, the design center in Copenhagen; he looked back fondly on taking a six-month internship in Brescia, Italy, at the factory belonging to designer Carlo Hauner, and was delighted to get a call from Oscar Niemeyer, who was calling from Milan, inviting him to arrange the settings for the home project he was designing for the Vice President of Brazil, in Brasília (which he ended up not doing).

Sergio was in love with his wife Vera Beatriz, loved having friends around, and enjoying a good meal in good company. He loved life with fervor. However, the death of his daughter Veronica, a partner of all hours at work and in life, stole the brightness from his eyes and made him depressed. Despite trying not to be down and maintain the humor that characterized him, Sergio got weak during a treatment against tumor and left little more than two years after his daughter. He left behind welcoming homes and environments, illuminated by his talent, and an extensive and definitive work, an enormous pride for Brazilians.

Caricature of Sergio Rodrigues in the Mole armchair.