"Sergio, you have no vocation at all [to be a priest], you'd better go out and take care of your life," said a friend of Sergio who was a priest.

“Sergio, you have no vocation at all [to be a priest], you’d better go out and take care of your life,” said a friend of Sergio who was a priest.

A while after she came back from Europe, Elsa married Dadi, as Zepherino Amaro D’Avila Silveira, a Rio Grande do Sul civil engineer, was also known. Sergio was 6 years old. Dadi was a childhood sweetheart, a distant relative of the Mendes de Almeida from southern Brazil who Elsa had dated when she was a girl and would go with her mother on vacation to the south. “He was delighted with my mother, though it was superficial dating.” Later, when Dadi found out Elsa was a widow, he began courting her. Dadi was so passionate that when Elsa told him she could no longer have children, he said: “Why should I want any more if I already have three of them?”. They were the sons of Elsa, among whom Sergio. “Dadi was wonderful to the boys,” says Vera Beatrice, Sergio’s widow, with whom he was married for over forty-one years, to the end of his life. Elsa liked to enjoy life, traveled a lot, and the greater responsibility in educating the boys ended up with Stella, their maternal grandmother.

Soon after the marriage, the family left uncle James’ house and went to a village near the Santo Inácio school. They moved into in a big house on São Clemente street, 254. Friends of his grandmother had two houses and lent one of them to Sergio’s family for them to live in. They stayed there a while. Grandmother Stella always took the lead in the boys’ care. However, in 1936, at age 9, Sergio developed a serious illness that would take away the games and affect him permanently. One day he went to sleep and would not wake up.

Sergio’s memories just before falling ill were good. There was a “June party” at number 254, the big house next to his, and at the Santo Inácio school, with much laughter and noise. But he went to bed early because of the firecrackers, which he hated. I was afraid of them, even of the small ones, and went to bed. He started dreaming in color, with many events. “With my eyes open as if I were awake, I looked ecstatic at the patterns on the curtains, which turned into Indians and dragons.” He and his sisters, who slept in the next room, had made a hole in the wall to chat through. (Incidentally, it is Sergio who says that the hole that appears so often in his creations “started there”). In the morning, the day after the festivities, his sisters started calling their mother, distressed. “They said I was going crazy, banging my head on the wall, as if I were epileptic.” He slept five days in a row, in a kind of coma.

The case was so serious that the grandmother, who was very Catholic, called a priest to give him his list rites, candle in hand. Doctors could not figure out what he had. He was unconscious. A physician then gave came up with the diagnosis: lethargic encephalitis. The doctor found that out had done his thesis on the subject and said that the patients usually either died or went mad. No case had been reported of someone escaping the disease. But he decided to give Sergio a new drug and, after five days, he woke up.

And he woke up as if nothing had happened. “The first thing Mom did was to suspend school until the end of the year. And it was just June. I loved it, it was a blast.” At that time, Sergio’s family was here and there. They would spend some time at grandma’s friend’s house, aunt Nina, and then at uncle James’. “That was the height of the mess,” recalled Sergio. But Vera Beatriz believes that the disease left sequela, emotional issues. Vera attributed the naiveté that always hurt Sergio’s business and caused him to not like talking about politics, economics, or other matters of this kind, to this sequela.

And life went back to normal. Sergio recovered, spent a few months having a lot of fun and playing games at home and returned to Santo Inácio, where he studied. Sergio had taken an admission exam along with his cousin Cândido Antonio (Cândido Mendes), who he considered “highly educated”, but did not pass. His Catholic grandmother had a dream: she wanted Sergio to study for priesthood and become the first Brazilian pope. She ordered a rosewood ring carved with the symbol of the Mendes de Almeida and told him: “You will wear it when you get the blessing.” And Sergio did. “I wore it and lost it on the first Sunday because I took it to the beach to show off to friends.”

In high school there was Aluizianum, the Jesuit pre-seminary. Those who had a calling went there. And in Sergio’s case it was because his grandmother recommended it. “It was Grandma who had a calling. The priest scolded me all the time. One day we made so much noise that the priest confiscated our ball. ‘You will have no football anymore.’ I called Grandma and said: ‘Go down to the Sete de Setembro street, at Valdemar’s place, and get a number four ball. Come here and throw it over the wall.’ And she did that. When the priest saw us playing ball again, he threw another fit.”

But there was another priest who was a friend of Sergio’s and was frank with him: “Sergio, you have no calling whatsoever, you’d better go on and take care of your life.” No sooner said than done. Sergio left the pre-seminar at about 14 years of age, but continued at Santo Inácio.

After graduating from high school, Sergio enrolled in CPOR (Preparatory Center for Reserve Officers – an option for military service). Perhaps because he was so afraid of popping noises, he asked to work in the artillery, handling canons, as perhaps he might lose his fear that way. And he did. After the first cannon shot, he was no longer so scared. After completing the CPOR, he joined a preparatory course to try to get into the School of Architecture. But where did he get that idea? One reason was prosaic: Pedro Correia da Rocha, the owner of the farm he used to visit as a teenager, had an architect nephew named Frederico Faro Filho, and Sergio used to make incursions into his studio, where there were enlargements of house prospects, designs, and drawings. That excited him. “I remembered uncle James’ drawings. I used to think architecture only involved house facades.”

But before that there was also that aviation thing, the desire to be an aviator. Another nephew of the owner of the farm, who was four or five years older than Sergio, had studied at Campo dos Afonsos, in the Air Force. Sometimes he would not come to the farm because he was flying in the Air Force. There was talk about aviation every night, and Sergio would fly on the pilot’s wings in his imagination. He wanted to blend his passion for aviation with his love of drawing. He then thought about designing airplanes, being an aircraft designer. “I also wanted to fly, but was more interested in drawing.” He went as far as taking the Air Force admission exam while still in high school, but did not pass. He went back to high school, graduated and took the entrance exam for architecture. He didn’t pass that either, as he failed math. But with the interference of his grandmother and the help of a supplementary list, he managed to get into Architecture.

From left to right, José Raja Gabaglia, Julio Delamare, Cândido Mendes, Cardinal D. Sebastião Leme, Sergio Rodrigues, and José Carlos Figueiredo, at Colégio Coração Eucarístico, in 1934.

Elsa Fernanda Mendes de Almeida Santos (Sergio Rodrigues' mother), next to Zepherino Amaro D'Ávila da Silveira (“Dadi”, Sergio Rodrigues' stepfather), in Rio de Janeiro, around 1960.

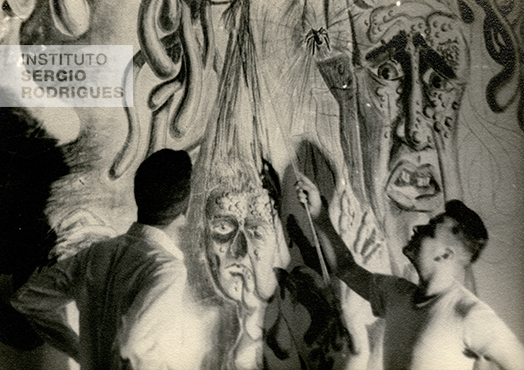

Sergio Rodrigues drawing a charcoal panel on the walls of his room at Castelinho, at Praia do Flamengo No. 72 - Rio de Janeiro, in 1947.

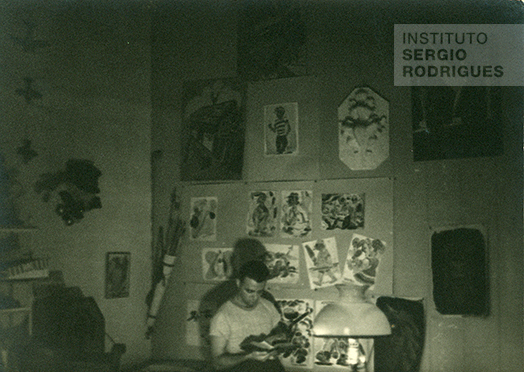

Sergio Rodrigues in his room at Castelinho, at Praia do Flamengo, in the 1940s.

Pipoca, Sergio Rodrigues' dog, at Castelinho, at Praia do Flamengo, No. 72 – Rio de Janeiro, in the 1940s.

From left to right, Mrs. Stella (Sergio's grandmother), Sergio Rodrigues, and Mrs. Elsa (Sergio's mother), at the graduation at CPOR (the Reserve Officer Prep Center), at the Candelária Church, Rio de Janeiro, in 1949.