Sergio entered Oca with the Mocho stool in his hand

Sergio entered Oca with the Mocho stool in his hand

The 1955 creation of Oca, the store that revolutionized the idea of furniture in Rio de Janeiro, was a major overturn in Sergio’s professional life. With no project to do and a family to support, Sergio arrived in Rio in late 1954, coming from his experience with Forma, in São Paulo, to try his luck. With “a corner” his father-in-law had offered him at his office, Sergio started working. But nothing worked out. He knew his future lay in creation; however, he envisioned creating a high-level store with top-notch furniture, something that would look a lot like Forma. With his prior experience, Sergio knew he could get in touch with major furniture makers. “I stuck my neck out and did it. That was when the great thing came up, which was Oca.” A store that was linked to the history of industrial design in Brazil.

The idea was great. However, I had to find a partner and a good place. Sergio started looking for a partner who could make his project feasible. He found the Italian count Leoni Paolo Grasselli. A natural merchant from Bergamo, Grasselli had a glassware shop in Africa and ended up coming to Brazil with Carlo Hauner. Sergio knew him from São Paulo. “He was enthusiastic about the idea and we took off to make history. I went head on to City Hall to speak with the authorities, and they agreed to talk. I thought it was possible to build a pavilion on the sand. And it almost was.”

Since Sergio never thought about money, but trusted work, he went in pursuit of possibilities. The first place that was suggested was on the Leblon beach. Not at the Delfim Moreira avenue, but on the beach itself, on the sand. They later found a piece of land at Chácara 92, between the Bartolomeu Mitre and General Urquiza streets, but at that time, free of buildings, the place was practically on the beach. At first, the proposal was to build a pavilion. Of course, you had to get permission from the City, know how it could be done, and if it would be legal to build a pavilion there.

It was all planned. Sergio had not only arranged the furniture from Artesanal that would be resold in Rio, but also from other major São Paulo firms. There were rugs, Dominici light fixtures, Italian furniture. “We were ready to go.” There was only a little problem: Where the money to fund the store opening would come from. Sergio believed the idea was so good that when people heard about the project, the money would appear.

They had a meeting with the owner of the land. He went directly to the subject. He said he liked the idea of renting the land for the store to be installed on it because he could not sell it, so Sergio offered him 10,000 Cruzeiros, which was a very good rate. But there was a problem: His relatives, also partners in the land, were “a little crazy.” “We tried to do something there several times, simple things, and they would come around and brake it all up the very next day,” the owner told Sergio. But he bet that when Sergio presented his project so firmly, he would have no problem building there.

Sergio was concerned. He knew that when they presented the project someone would offer the construction, equipment, and furniture free of charge to him and his partner. Even Coca Cola and Kibon were offering conditions. But he did not want to take a chance. He said to his partner, Grasselli, that they should not do it because they would be held responsible if anything happened. “The cure would be worse than the ailment.”

The man, according to Sergio, got a little desperate, but he understood. So they went looking elsewhere. At the General Osório Square, in Ipanema, more precisely on Jangadeiros street, a building had just been built and the first floor, which led to the square, had already been nearly entirely rented out. There was only one store left to rent, and it was empty because it had a pillar almost smack in middle of the display window. Shortly thereafter, Sergio bought the store with the inheritance his grandmother left him.

Even before he saw the space, Sergio said: “Let’s rent it anyway.” It was a good, large space, but Grasselli found it odd that there was a pillar right in the middle of it. Have a store with a pillar right in the middle of it? But Sergio insisted, and they went to work. The store was inaugurated on May 10, 1955. “Even my mother helped me. She sewed a big blue canvas that we used to make the ceiling lowering. It was a wonderful time. It was a golden age.” He said Oca was inaugurated “with all courage.”

But Oca had to be different. Even in its name, which was conceived an afternoon at Grasseli’s apartment in Arpoador. Sergio did not want Sergio Rodrigues Office, as Grasselli had suggested. He wanted a name with few letters, one that expressed the Brazilian interior architecture. And he did not want to simply create a furniture warehouse. He wanted to give customers the idea of a whole.

To achieve this, he created true scenarios and environments inside the store. To make up the shop window, Sergio invented a wooden puppet who dawned in a different position every day, sitting in armchairs or chairs, showing people passing by how comfortable the furniture was. The doll was a big hit.

At first, Oca sold furniture made in São Paulo, but before long Sergio’s creations came to occupy most of the space. In addition, Oca also sold innovative Dominici light fixtures and beautiful fabrics designed by the artist Fayga Ostrower. With support pouring in from architects who saw in the store a new option to organize the settings for their interiors with good commercial acceptance, Oca grew rapidly on the market.

On the opening day, Sergio walked into Oca carrying the Mocho stool in his hand, the one he had created just under a year before, in 1954, and would become an icon of his work. That was where Mocho, which in 2014 turned 60 years old, began its long and brilliant career. The Hauner couch, which he had drawn in São Paulo, was taken to the store already at its opening and would be Sergio’s second piece to enter Oca.

“The opening was a huge hit. Jaime Mauricio was the trendiest art critic of the time, he was a friend of Carmen Portinho, from Burle Marx, and of Guiomar Muniz Sodré, from Museum of Modern Art. He loved Oca, he was always there. The store got full pages in newspapers. There were two pages in Correio da Manhã. It was a scandal. It spoke about the opening of the store, about me, Grasselli.” The opening party was sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art (MAM). “It was a really big thing.”

Sergio took care of furniture arrangements and of the store’s general decor from the beginning. It was a store unlike any other, with a scenic arrangement coordinated by Sergio. Since at the time there was nothing with the modern atmosphere that the store got, Oca was a hit in no time at all. “Not a day went by that someone didn’t talk about Oca. It was spontaneous, we never paid a penny for promotion.”

The work Sergio did at Oca was a manifestation of the effervescence of the Brazilian culture in the 1960s and ended up representing the “struggle for a truly national, contesting art,” wrote Maria Cecília Loschiavo. And what the furniture contested was excessive formalism, delicate stick feet that gave way to the “stupendous strength of Brazilian wood.”

Sergio did a thousand tricks to publicize Oca. The greatest of them was the idea he had to photograph some of the shop’s furniture, including the Mole armchair. The photographer was Otto Stupakoff, one of fashion photography pioneers in Brazil, the same who had ordered a creation that eventually became the Mole armchair.

“Otto Stupakoff ordered a couch for his studio, which was tiny. The sofa would be a piece to be used for resting. The idea was for it to be there for the person to feel at ease on. He paid for the piece by photographing it for Oca’s first catalog,” recalled Sergio.

They set out to photograph the furniture. The set? Nothing other than the Leblon beach. It was very funny. We put the piece on the sand, at the end of Leblon, which was quiet at that time, three o’clock in the afternoon, it was deserted, there was a flat, even surface, an infinite, wonderful background, since he had neither an infinite background nor a specialized studio. But there came a naughty wave and all of the furniture got wet. It was funny, because at the time there was a lot of anxiety. But the next day, the exhibition with the Mole armchair was inaugurated with remarks in the press that stated that we had thrown the furniture to the sea, as if it were a kind of black magic,” said Sergio to the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, in February 2006.

Sergio’s goal, as was that of Lina Bo Bardi and other architects of the time, was to make pieces compatible with the modern Brazilian architecture. Sergio bet all his tokens on Oca, which was more than a store. It was a blend of a shop and art gallery and, in a very short time, became the place of gathering of Rio’s intelligentsia.

On that same street, Jangadeiros, next to Oca, there was the Silveira Sampaio theater, which was already a gathering place for intellectuals and artists. Since the theater was very small and there was no room in the foyer for people to wait for the performances to begin, Oca started being used as a meeting place. The store stayed open a little later, and the theater audience filled the sidewalk and the spaces between the furniture.

Seeing such an enthusiastic audience, both of the theater and that the store itself had won over, Sergio decided to organize events and exhibitions at Oca. Almost all the known artists of the time exhibited there. In addition, the store started attracting young and talented architects, among whom Bernardo Figueiredo, Marcos Vasconcelos, and Dolly Michailovsky. They all designed furniture for the store and Sergio supported everything they did.

The bet on Brazil was clear from the name Sergio chose for the store: Oca. “The simple choice of name defines the meaning of the work Sergio Rodrigues and his group did. Oca is the house of a native Brazilian. The house is structured and pure. In it, utensils, equipment, personal gear and vestments articulate in everything and integrate with formal precision as a function of life,” wrote the architect and urban planner Lucio Costa, the first to note the presence of this character of Brazilianness in the designer’s work.

“When I imagined opening a shop that represented Brazilian furniture, I came up with a name that was, in a way, enough to determine what I had in mind,” said Sergio. “So I did not use my name, as one would imagine, of course, for the production company, because that is not what it was all about. I used a name that could add value to the work of other designers and materials. That was what Oca was about. And, in this case, the starting material was, naturally, Jacaranda.”

Shortly after the opening of the store, Sergio began to go deeper into his most famous creation, the Mole armchair, which he released two years later, in 1957. Made of Jacaranda, the model had a top cushion divided into four interrelated parts and soon drew attention for its innovative features. What was going on there, as said journalist Adélia Borges, was “the gestation of the truly modern Brazilian furniture.” In 1961, Sergio, who did not much care for self-promotion, because of great insistence of then Governor Carlos Lacerda, ended up entering his Mole armchair in the IV International Furniture Competition, in Cantu, Italy. Sergio won the contest in which 27 countries and 438 competitors took part.

The competition involved big names in the international design scene, and the jury justified granting the award to Sergio: “The only model with current features, despite its structure with conventional treatment, not influenced by fads and absolutely representative of the region of origin.” It was the first international award ever granted to a Brazilian design.

Façade of the Oca store at Rua Augusta, São Paulo, where the office furniture line that was characterized by its modernity used to be sold, in the 1960s.

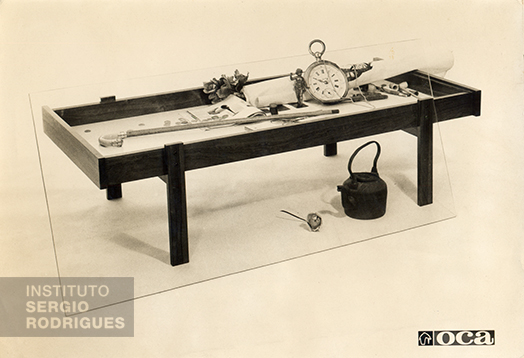

Vitrine auxiliary table, created by Sergio Rodrigues in 1958; it was made out of solid hardwood, with the bottom of the box made out of white melamine or felt and with 10-mm crystal top.

"Mole" sofa photo shoot on the Leblon beach, in 1958, made to publicize Sergio Rodrigues' work. However, the tide went up during the photo shoot and doused the piece, which was still a prototype.

Logotype of Oca, created by Sergio Rodrigues in 1955.

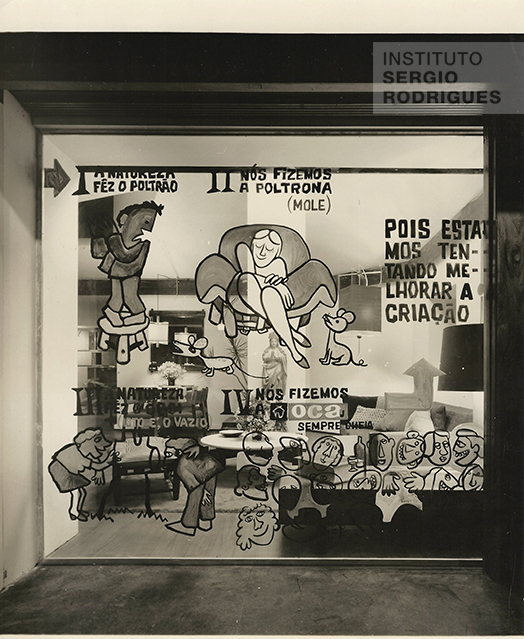

Display window Millôr Fernandes created for the Oca store, located at Rua Jangadeiros No. 14 - store c, Ipanema - Rio de Janeiro, in 1965.

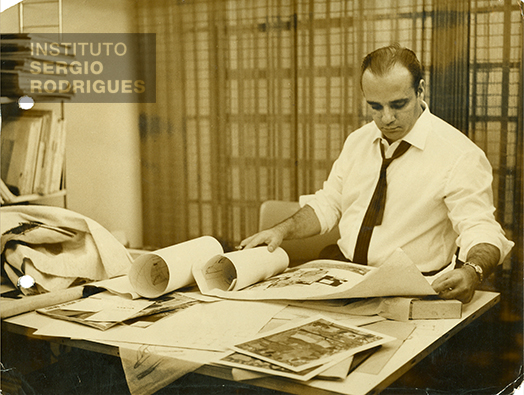

Sergio Rodrigues, at age 39, in his office at the Oca, located at Rua Jangadeiros No. 14 - store c, Ipanema - Rio de Janeiro, in 1966.