His father's death remained a mystery to Sergio for a long time

His father’s death remained a mystery to Sergio for a long time

The earliest recollection Sergio had of his childhood was the scene of his father and mother sitting on the couch that he could see from his small bed. This was one of the few images he kept of his father, Roberto Rodrigues, who was murdered when Sergio was but 2 years old. He could also remember his father riding a horse in cowboy dress, and his mother, also on horseback, riding with his father on a farm belonging to a few family friends in Cabo Frio, where Sergio was taken to gain weight soon after he was born.

Roberto Rodrigues was born in Recife and came to Rio de Janeiro quite young with his mother, Maria Esther Falcão Rodrigues, and father, Mário Rodrigues, Sergio’s grandmother and grandfather. The Pernambuco patriarch of the Rodrigues clan and a well-known journalist in Recife, Mário worked at the Diário de Pernambuco newspaper when he had to move permanently to Rio de Janeiro, in 1912, on account of political issues. He moved there with his wife and sons, Milton, Roberto, Mário Filho, and Nelson. Mario was considered one of the most courageous Brazilian combatants and journalists in the early twentieth century.

Upon arriving in Rio, the family went to live on Alegre street, in Aldeia Campista, a district later absorbed by its neighbors Andaraí, Maracanã, Tijuca, and Vila Isabel. In the capital city, and after a tumultuous period at the Correio da Manhã newspaper, with political charges and a small stint in prison, Mário founded his first daily in Rio, A Manhã, in 1925, in which he was a chronicler of destructive rhetoric. One of the most feared chroniclers of his time, writing bright and hurtful articles, Mário revolutionized journalism, but his corrosive style eventually turned against him and led to a great tragedy in the family.

According to the Biblioteca Nacional Digital do Brasil portal, A Manhã was “a versatile 12-page morning newspaper published in standard size, with a good layout and making good use of images (…). An embattled critic, he a used scathing, pamphleteering, demagogic, humorous, and accessible language. He confronted authoritarianism, the oligarchies and the political structure of the Old Republic, pursuing commitment to popular causes.” Therefore, Mário Rodrigues was feared for his bold journalism, which displeased many. In his day, he was considered one of the most courageous Brazilian combatants and journalists in the early twentieth century.

In Rio, Mário and Esther had other sons and daughters (14 in all) and Roberto went work with his father as a newspaper illustrator at an early age. He had studied at the School of Fine Arts, and was considered an expert drawer. Robert’s family was one of artists and intellectuals. Nelson Rodrigues, Roberto’s younger brother, transitioned from journalism to drama, becoming one of the most celebrated Brazilian authors. But Roberto did not live to witness this fame, as he died tragically at a young age, when his brother Nelson was 15.

Between paint brush strokes and drawings at the School of Fine Arts, Roberto, a seductive, handsome young man, a good writer and gifted illustrator, a true Rudolph Valentino of the time, fell in love with Elsa Fernanda Mendes de Almeida, who was also taking classes at college, as a listener. That was the only way her family would allow her to go to college. The only granddaughter of Fernando Mendes Almeida, a member of a Catholic family that was part of the Rio de Janeiro high society, of intellectuals linked to the Church, among whom Dom Luciano Mendes de Almeida later stood out, Elsa had to face her family’s opposition to her relationship with Roberto. Her family did not want her to marry someone coming from a family with such a bad reputation. But the unexpected pregnancy resulting from a great passion sealed their marriage. Sergio could not help comment what happened with humor: “I do not know the details, but it is said I had been made before the marriage. It is somewhat hazy.”

After leaving A Manhã, Mário founded A Crítica, in 1928. It was at this newspaper that some of his kids debuted in the journalistic career. When he owned A Crítica, he was arrested again and convicted on account of an unsigned story in which Pernambuco mill owners were denounced for giving the then First Lady, Maria Pessoa, a diamond necklace. Mario served his sentence and returned to the newspaper. His aggressive style permeated the newspaper’s editorial line, and he himself once even said that “someday someone from A Crítica was sure to be shot dead.”

No sooner said than done. One day, in 1929, the newspaper published a story about a noisy divorce case, at a time when marital separations were taboo. A Crítica announced the divorce of Sylvia Serafim and João Thibau Jr. with fanfare. Sylvia could not take the scandal and walked into the newspaper’s newsroom, gun in hand, ready to kill Mário Rodrigues. Since Mário was not in, she was met by Roberto, his son. Sylvia did not give it a second thought and shot Roberto, who died three days later, at age 23.

As said, Sergio was only 2 years old. Elsa could not attend the funeral. His grandfather, Mário, who could not bear the pain of losing a child to a bullet intended for him, started drinking heavily and died four months later.

His father’s death remained a mystery to Sergio for a long time. His mother’s family moved him away from his father’s relatives hastily and would always change subjects when Sergio asked about his father. Sergio’s sister, Maria Teresa, was only a year old, and the other one, Vera, never even got to know her father because Elsa was three months pregnant when Roberto died.

Sergio could not accept to know nothing about the circumstances of his father’s death. It tormented him so much that, at age 17, he went to the National Library, in Rio de Janeiro, to search for information. He researched newspapers of the time tirelessly. And then he learned the truth. A Crítica had published numerous editions on the crime, which became a scandal in all papers. Sergio was disgusted with the article that caused the tragedy. The note about the woman who was getting divorced featured a drawing that Roberto had made at Mário’s request to illustrate the story. Although he remembered very little about his father, a memory had set in Sergio’s mind of a scene that only came to light in a session of psychoanalysis, many years later: Sergio was taken to his father’s funeral and put on top of the casket.

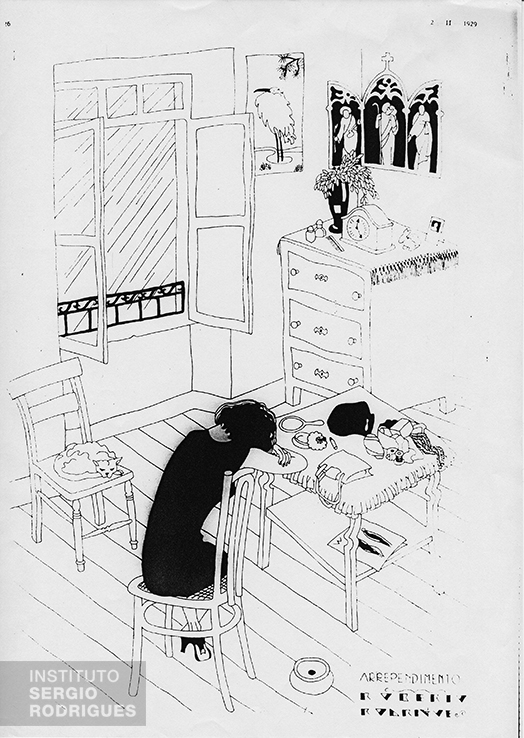

Despite the very short amount of time he spent with Roberto, Sergio always admired his father’s strong, stylish lines, which he used in his paintings and drawings, in scenographic screens for vaudeville or to illustrate newspaper stories. But what stuck in Sergio’s emotional memory of his father’s work was, according to Maria Cecilia Laschiavo, “his sensitivity to capture, handle, and represent aspects of the collective imagination with fluid lines and the taste for things of the earth.” No doubt a legacy he left Sergio.

Roberto Rodrigues (father) in Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, in the 1920s.

Self-portrait of Roberto Rodrigues (father) in 1928.

Roberto Rodrigues (father) with Sergio Rodrigues (at age 1) at his residence at Rua Joaquim Nabuco - Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, 1928.

Photocopy of an illustration made by Roberto Rodrigues for the Para Todos Magazine, in 1929.

Rodrigues family, from top to bottom, from the third row, Milton, Nelson, Joffre, Maria Esther, Mário, Mário Filho, Célia, Stella, Roberto, Augustinho, Elsa, Maria Clara, Irene, Helena, Paulinho, Sergio, Elsinha, and Mário Júlio; in 1930s.