He had been looking for some port from where he could sail and drop his ships. Over time he understood that what he was looking for was a specialized course in interior architecture.

He had been looking for some port from where he could sail and drop his ships. Over time he understood that what he was looking for was a specialized course in interior architecture.

The University of Brazil’s National School of Architecture still operated, for the last year, at the building of the National School of Fine Arts, in Rio de Janeiro. To Sergio, everything was very pleasant in college, and he said it was a “very nice” period in his life. The only thing that bothered him was math. He could not “operate” properly in that subject and benefited from the patience of his renowned math professor, Júlio César de Melo e Sousa, known for the Malba Tahan heteronym, which was how he used to sign his books, including the famous The man who calculated. Sergio says Malba Tahan allowed him pass in math every year, but only barely.

Over time, Sergio started liking architecture. He was very fond of a professor who was very knowledgeable in art history, and Sergio was deeply interested in that subject. But he had been looking for some port from where he could sail and drop his ships. Over time he understood that what he was after was a specialized course in interior architecture. He was studying the early part of architecture and wanted to dive into decoration and the styles of all eras.

Therefore, his great interest at that time was in interior decoration. In fact, he was always interested in this, ever since he discovered the wonderful world of his uncle James’ workshop, as a kid growing up at number 72, as he called his uncle’s place. All of the furniture in it was European, and Sergio found it very interesting: lamps, armchairs, chairs, tables. At the workshop, which was in the backyard, uncle James repaired furniture. Sergio paid attention to the slots and made his wooden toys using joinery techniques that he learned from his uncle’s woodworkers. He also liked to make arrangements.

His aunt Zita, uncle Pericles’ wife, used to always ask him for help with her flower arrangements. “Boy, you have the hang of it!”, she would say. And he would get excited about it.

Sergio then found out that the study of Interiors was part of the college’s curriculum. However, it was not very explicit. “It was not complete, and I was dying to have it all.” His gift and interest led him to look for a book or some other school that would teach him so he could go deeper into the Interior issue that fascinated him so much. He was a junior in college. It was no easy task. He did visit Singer Decorações, but when we got there he found that there was only a group of women working with sewing machines. Singer machines, of course. He sat there for a day, watching. He thought someone might explain styles and arrangements to him, but soon realized that was not what we wanted and left.

He continued his search and soon saw an ad: “Home Decorations, professor Louis Earl James.” That would be another James in his life. This one was a Jamaican who had studied in the United States and returned after taking several courses. Interior design courses: furniture models, styles, arrangements. He also decorated for customers. He taught in a room at Churchill Avenue, downtown Rio de Janeiro, and all of his students where female. “He would show fabrics he brought from the United States and women would go crazy. They were only interested in that. But he soon realized that I was really interested in the classes.”

One day the teacher told Sergio he only knew how to arrange environments of one style. “I cannot do anything modern, but you do modern in college,” James said to Sergio. He said that and invited him to be his assistant and help out with the modern concept. Sergio gladly accepted. The work included travel to São Paulo and tasks in Rio de Janeiro. Sergio liked that, and did it along with his studies. He even created two or three pieces during its course.

In the same period, he met Decorative Composition Professor David Azambuja at college. He signed up for his class and dove deeper into this area. He was so interested in it that Azambuja invited him to be his teaching assistant. Thus, Sergio took both Azambuja’s class in college and James’ class at the same time: “I would average the two out and go deeper into the matter.” That is how it was until he graduated.

Architecture took place in parallel. Sergio was frustrated to see almost all his colleagues taking internships at architecture firms and being unable to get one. He would go from one place to another with plants, designs, and drawings under his arm in hopes of finding a place to “do, see, feel environments that knew architecture or creation.” (Casa e Jardim magazine, January 1985). He then decided to rent a room with a group of friends. Each person would only take his own materials there. Sweet illusion. Nothing happened.

But the answer he wanted would come soon after. It was just before Sergio graduated from college, when professor Azambuja, a well-connected native of the state of Paraná, was hired by Bento Munhoz da Rocha, then governor of Paraná, to create the Civic Center of Curitiba, a kind of mini Brasília, with a government palace, buildings for the state departments, the Palace of Justice, and everything else. Azambuja did not give it a second thought. He called Sergio to take part in the work. Olavo Redig de Campos and Flavio Regis do Nascimento were also summoned.

Sergio agreed, of course, and thought he would serve merely as an assistant in the project. But that was not how it went down. Sergio had no idea that he was going to do architecture and be put in charge of creation, but each architect was vested with a mission. Azambuja gave each one a palace to work on. When they went to sign the contract, the governor saw Sergio among those older, more experienced architects and asked: “And what about that kid over there?”. The professor replied: “He’s no kid, he is in charge of the departments.” Sergio nearly fell off his feet. The departments? “I was just a boy, almost a pirate’s parrot. I hadn’t even taken my final exams at college yet. But I went.”

It was determined that the offices would be at the head office where the Civic Center would be built. Sergio had his helpers and would take part in the project on an equal basis with celebrated architects such as Olavo Redig de Campos, Flavio Regis do Nascimento, and David Azambuja.

He would be in charge of designing the Departments palace, a 33-floor building, and the dome of the State Payment and Receipt building, the calculation for which, made by the engineer Paulo Fragoso, would turn it into one of the boldest “concrete shells in the world.”

But despite the responsibility and of having been given a grown-up’s task, Sergio would earn half the others’ wages. Because “he was a boy.” They made 40,000, while he, 20,000. At the time, it was common for an architect to make 5,000 to 10,000. Although he thought Azambuja would “keep a lot of the money for himself,” Sergio agreed and thought: “So be it, whatever God may want.”

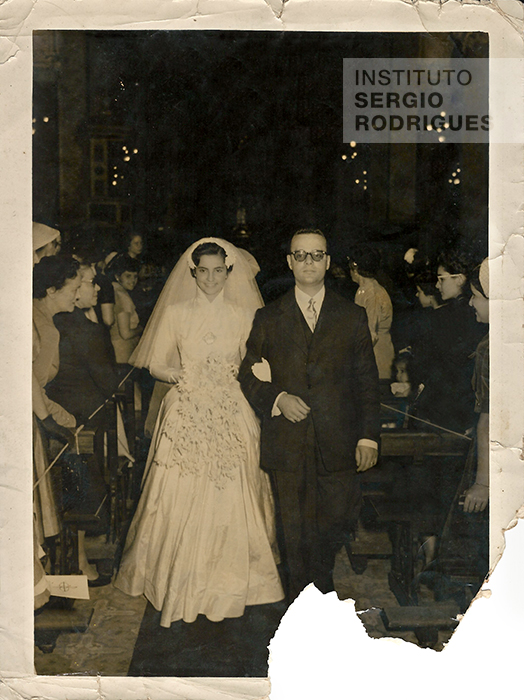

He returned to Rio and took his final college exams. He was gearing up to marry his girlfriend, Vera Maria Serpa Campos, because he had started having ideas. If he was going to make 20,000 and the work would end one day, he should better marry his bride, who was 17 years old. That was when, at the eve of his wedding, Azambuja came in and brought him a bundle of money. “Here’s all the money I saved for you.” “He thought I was going to do something silly with the money and saved the other half for me. It was a lot of money.” The “savings” he was unaware of helped him materialize his marriage.

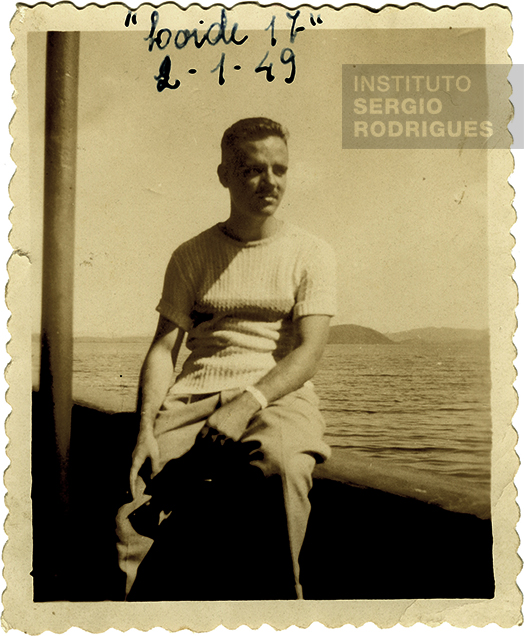

Sergio Rodrigues, at age 22, on the Lloyde Brasileiro vessel, on Jan. 02, 1949.

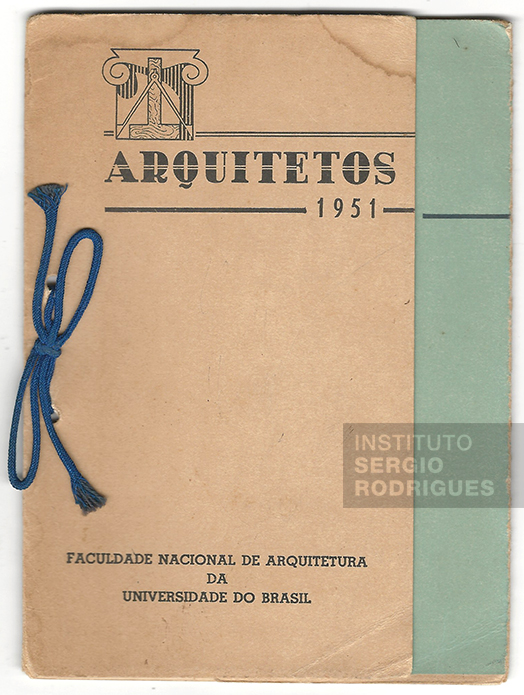

Invitation to Sergio Rodrigues' graduation at the University of Brazil's National School of Architecture (today the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro's College of Architecture and Urban Planning - FAU/UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, 1951.

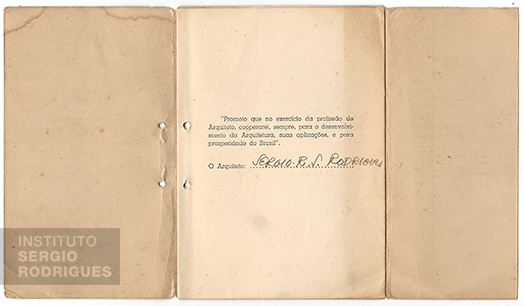

Invitation to the graduation of the College of Architecture at the University of Brazil (today the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ), featuring an oath signed by Sergio Rodrigues.

Religious ceremony of Sergio Rodrigues' first marriage, with Vera Maria Serpa Campos, in 1952.