"A good architect must understand the human dimension of his invention." (Fernando Mendes de Almeida)

“A good architect must understand the human dimension of his invention.” (Fernando Mendes de Almeida)

Sergio often repeated a phrase: “Architecture defines itself from inside out. The facade is just the result.” Your way of seeing the house, the setting, has always been looking from inside out. Its architecture was designed for life to happen in there, based on an idea of harmony that the environment could bring to people. Settings are planned in detail in his drawings. It is not uncommon to see illustrations of activities taking place inside homes or objects that could contribute to the understanding of everyday life in Sergio’s drawings. For example, a drawing of a stool for one to put on a shoe on or a reading lamp next to the chair appearing in the middle of an architectural blueprint. When designing a beach house, he drew a woman wearing a bikini in a room who you could see through the open window. They were always drawings of people or objects falling into place in the setting, keeping coexistence in the house in mind.

But the architect was always in contact with the designer in Sergio’s work. To Fernando Mendes de Almeida, one of his main professional heirs, construction, in his architecture, always involved the idea of fitting in. “Not in the sense of joinery fitting, rather pillars and beams. He always thought up settings in which objects seemed to be characters. It was all done considering coexistence. Nothing was disconnected from affection. It was not enough for an architect to plan and study his creations technically. To be successful, he needs to understand the human dimension of his invention.”

Sergio’s architecture was full of elements and always thought through play. The house he built for his family in Petrópolis had a skylight, mezzanine, and stairs in the Santos Dumont style that led to a loft that was open to the living room. His room had a window looking out and another one looking in. It had high ceilings. “It was almost like a big game, but made with the utmost seriousness, just as serious a game is for the child,” says Fernando.

The connection between architecture and interior design comes from the time that chairs used to lean against the walls and completed the design of the building as if they were columns or elements of the actual architecture. This can be seen, for example, in the

Crystal Palace, in Versailles. There, the chairs, furniture, sofas, armchairs, auxiliary tables, all positioned against the walls, form an architectural complex with these walls. Sergio brought the concept that interiors should be connected to architecture into his training, a fact often overlooked by architects.

To Fernando, Sergio always had a calling for furniture. “He said he saw a very advanced movement of Brazilian architecture with the modernist movement, and that interiors did not keep pace with this modernity. Interiors continued being filled with colonial or imported furniture. They lacked this modern furniture. He had this vision, this intuition, and invested in it, and it ended up being his main route. His architectural view is very interior.”

Sergio was aware of this. He revealed this thought in an interview with critic Afonso Luz: “I used to think, since I studied architecture, I am architect, and I like wood and furniture, that prefabricated architecture, made in a workshop, was design. So, prefabricated architecture, the output, is design because you have the qualities needed for design and it is actually it that equips architecture to perform, that equips this space with elements characteristic of what has been created for a given function, such as the solutions that were given to the furniture.”

In 1975, Sergio won the prize of the Brazil Institute of Architects, in Rio de Janeiro, with the Kilin armchair. At this point, home, hotel, and office projects were already gaining space in his career. From 1977, several architects and designers often collaborated with Sergio in his prototypes, people such as Freddy van Camp, Arthur Jorge de Carvalho, and Lucinha Redondo. From 1980, house and interior ambiance projects once again went on to count on the collaboration of Dolly Michailovska. After working with Dolly, Veronica became the main contributor to Sergio in architectural projects.

The SR2

From the desire to build a country house on the land of his father-in-law that could be transported in the event of a move, in 1959, Sergio started making the first studies for the SR2, a system composed of prefabricated wooden elements for building housing architecture. Sergio first thought of a structure made of galvanized iron pipes coated with plywood. Then, of course, he arrived at wood. He made these projects outside of Oca, and worked into the night, Sundays and holidays, to find the solution.

When seeing Sergio’s study material, the then director of the Museum of Modern Art (MAM RJ), Niomar Muniz Sodré Bittencourt invited him to make an exhibition at MAM, in 1960. Thus, in fewer than twenty days, the first prototype of a modernist house designed by Sergio and built at MAM was born. It was not a prefabricated house with a ready-made project, rather a building system attentive to the customer’s program. The prototype measured 50 square meters and had great impact. There were standard pillars, beams, closing panels, and this house was built as if out of Legos. The piece was assembled with predetermined panels. Lucio Costa said in a letter to Israel Pinheiro – who was responsible for building and, later, the first administrator of Brasilia – that that would be the only wooden house that could be built in the new capital because the master plan did not allow wooden houses.

From 1962 to 1967, Sergio put into practice his studies on the SR2 system in buildings such as the Brasília Yacht Club and two pavilions to lodge teachers and restaurants at the University of Brasilia, at the request of Darcy Ribeiro. More than 200 houses were built with this system until 1968, and at least 70 were taken from São Paulo to the Amazon in Hercules aircraft and assembled in the forest to serve the Humboldt Research Center.

The SR2 was also used in Goiânia to build houses and clubs, and, in 1977, in partnership with the Danish architect Leif-Artzen, Sergio undertook a study for export for use in extreme Nordic country temperatures which was called Modu-Home.

In the beginning, the more than 200 houses that had been designed had a flat roof. Some time later they were made with sloping roofs. Only the former had flat roofs, such as some he made in Brasilia. Sergio worked with the project in three phases. In 1980, he returned with the SR2 with the construction of his own house in Petrópolis, and another one in Brasilia. He stopped again, and resumed construction in 1993. He made many homes after that.

Sergio’s work as an architect was relatively overshadowed by his notoriety as a furniture designer, but the exhibition of the prototype, in 1960, kick-started the production and assembly, in that decade, of hundreds of units, including houses, housing projects, hotels, clubs, restaurants and outpatient centers. In 1982, Sergio participated in the Design in Brazil: History and reality exhibition at SESC Pompéia, in São Paulo, which paved the way for the revitalization of the SR2 System, in 1984.

Despite having been more noted as a furniture designer for a long time, Sergio made sure the that seal placed on his furniture brought the inscription Sergio Rodrigues, architect, Brazil. Architecture was believed to be more prestigious. Sergio used to say: “I design furniture, but I am architect.” Nevertheless, Sergio never had any affinity for the so-called high architecture. According to Fernando Mendes, it is not his way of being. “He likes simplicity, warmth, he is good-natured, playful, likes the informality that is not the language of this high architecture.” Later, Sergio went on to sign only as Sergio Rodrigues, Brazil.

Throughout his life, Sergio never lost his humor and savoir vivre. However, in 2012, just over a year before his death, he suffered a setback which left him bitter. He lost his daughter Veronica, who worked with him for many years in his architectural office and was his right arm. They were very close and he considered her his heir in this area. Talented, following in her father’s steps professionally, Veronica took part in all of Sergio’s architecture projects and the two used the same language. “Veronica proved to be an excellent architect. She was the continuation of Sergio, his right arm and a great companion. Sergio viewed his continuation in her,” said Dolly Michailovsky. To Vera Beatrice, Sergio’s widow, “she inherited her father’s creativity. Even while ill, she still worked and taught at PUC, despite feeling sick. I have never seen anyone with such a fight in them,” she said. It was a huge blow. Sergio was very shaken by the death of his daughter, and never fully recovered from it, although he always tried to keep his humor and his light way of being.

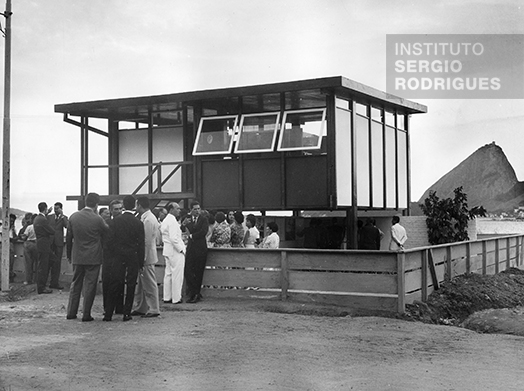

Photo of the mockup of the house made using the industrialized architecture in wood SR2 System.

"Individual prefabricated house" exhibition where Sergio Rodrigues presented the prototype of the industrialized architecture in wood SR2 System at the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art, in March 1960.

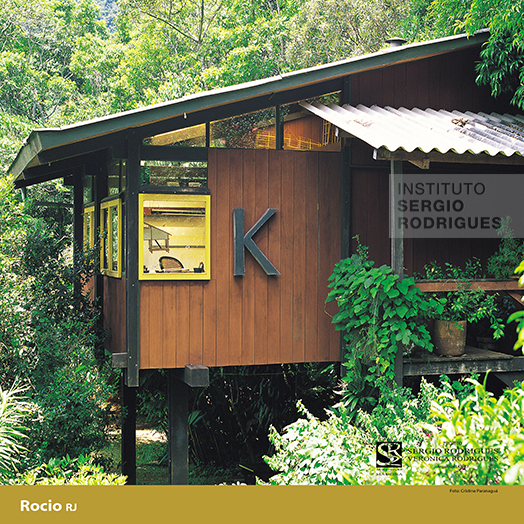

Xiklin house, built using the industrialized architecture in wood SR2 System, at Rocio, in Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, in 1983.

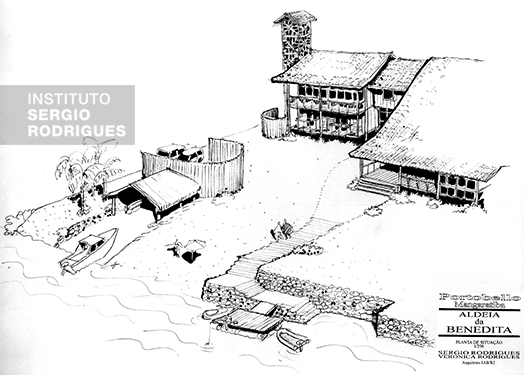

Drawing of the "Aldeia da Benedita" project, built using the industrialized architecture in wood SR2 System for Regina Casé in Mangaratiba, Rio de Janeiro, in the 1990s.