Sergio wanted to exhibit more than furniture: He wanted to showcase the author's face too

Sergio wanted to exhibit more than furniture: He wanted to showcase the author’s face too

The existence of Oca and the way products were presented there, with the designer’s name and the material used, paved the way for the author to gain a leading role in his product’s creation. When Sergio started designing furniture there was no recognition of the author in Brazil. “The first moment of Brazilian design is marked by a design that has no author. This shift in paradigm is a very recent thing in history, beginning perhaps some time about twenty years ago,” says researcher and art critic Afonso Luz. The author started emerging as a central element in design from Sergio’s creations, but also very much so due to a practice he adopted at Oca, where each piece showed the author’s name and the material used. This trend was even more evident in the exhibitions he organized at the store. “I intended to showcase more than the furniture,” said Sergio, who wanted to show much more than the product.

From the moment we opened our doors, the store started innovating. They soon began to use Oca’s space to exhibit works of plastic artists, but also to experiment in design. One of them was the famous Furniture as an Object of Art exhibition Sergio invented and coordinated.

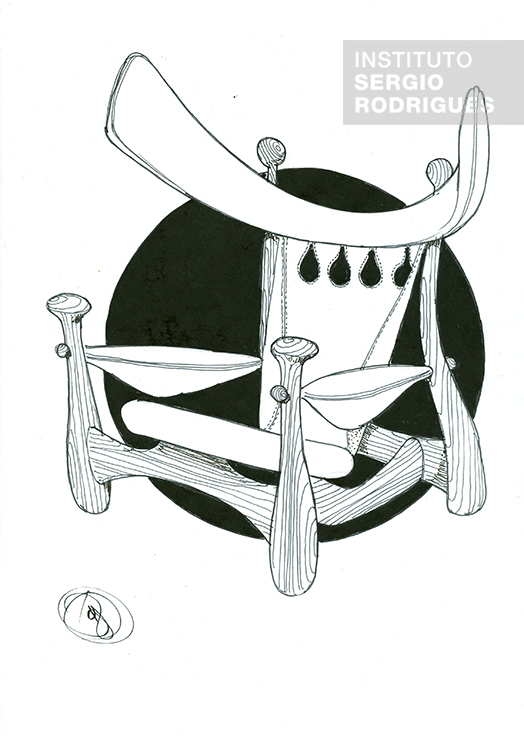

To Afonso Luz, this exhibition “is one of the most important historical references to the idea of author design, even internationally, an exhibition that greatly anticipated this contemporary trend, (…) that look that sees design as art.” To him, the Chifruda armchair, which appeared at the exhibition and was born and baptized as “Aspas”, and is a milestone of that.

The exhibition was born from a disquietude of Sergio. The year was 1962. At that time, the Mole armchair was already in production, although Sergio thought it had not gotten adequate commercial support. Something that happened long after with all of his work. Sergio believed furniture creation used to be taken for granted, unlike what happened with someone who painted a picture or designed a rug. “To me, people did not consider furniture as an object of art. Magazines, the media, only discussed indoor settings. They cited the paintings, the authors of the paintings, of the rugs, they discussed the material used, spoke of everything, but never mentioned the furniture. They said nothing about the bed, the sofa, the armchair, as if such objects had not been someone’s creations.” They even discussed the fabrics, coating materials, but never who designed them. That bothered him. “They never gave proper attention to that. I wanted them to pay this attention.”

Sergio also had another concern. He thought it was necessary to show the authors’ faces. “We knew the face of practically all foreign creators, but didn’t known Tenreiro. Nobody knew what Tenreiro looked like. Nobody knew what many established authors looked like, despite all their importance. There was much talk about Tenreiro, but this figure was never shown publicly. So I wanted to do things differently, my intention was to exhibit not only furniture, but the author as well.”

With this idea in mind – of showing something about the author that could reveal who he was, citing his activities and peculiarities – Sergio started organizing the exhibit. He wanted to invite young students. But also renowned creators in Brazil, some made famous with the construction of Brasilia, others known abroad, such as Lucio Costa, Sergio Bernardes, Alcides Rocha Miranda, Marcos Vasconcelos, and Bernardo Figueiredo. So Sergio invited this group of architects to make pieces for the exhibit.

But how to do it? All guests were famous architects, not designers. Sergio then asked them not to worry because whatever they created would be developed by Oca, at Taba, the factory that Sergio opened to make his furniture. The authored furniture was taken to the exhibition together with the author’s name, origin, and characteristics. The exhibition blended new talent and big names. Celebrity guests included Oscar Niemeyer. But the great architect of Brasilia at the time was preparing a few pieces for the Brazilian capital and was unable to present his project. There were other important names too, of the likes of Lucio Costa.

Oca’s technical and creative support was key. As was the case of Lucio Costa, who created two pieces, a small and a regular chair. Although he had a lot of experience in architecture, Lucio Costa did not feel confident with what he had created. He said Le Corbusier himself had made one of the pieces and that he was copying the master. But Sergio reassured him: “What? Le Corbusier never made a piece out of wood like that. No. I myself have made this chair back and it has nothing to do with Corbusier.” There was no true distinction between creation and what the development of design was in a piece of furniture. Sergio went further: “Mister (which was how he addressed Lucio Costa), you are saying that you copied Le Corbusier, but I say that Le Corbusier copied a Danish author. He did not create, rather he developed a chair that had already been created in the middle of the previous century, since in the nineteenth century there was a chair like this that was part of the products of war of English colonization.”

Sergio was fascinated by Lucio Costa’s humility and helped him find solutions and get where he wanted to be with his furniture. “He was delighted. The armchair was made and it is a wonderful thing – the small Lucio chair.” Lucio’s second piece was a small, four-legged, round seat chair. When Sergio saw the drawing, he said: “This chair will not stand up.” Sergio knew that conceiving a chair and developing it were two different things because development demands knowledge and experience. But he tried to help. Even so, the chair would not stand up. So a prototype was made. Lucio Costa thought it was funny and said it was easier to build Brasilia than to make that chair.

“The chair did actually collapse, and would not stand on its own. I never talk about it because it may give the impression that I am making fun of him. But I did not want to interfere. ‘You see? Lucio made a chair that would not stand on its own!’. And I did not want to interfere, that was not the goal, I just wanted to help. His simplicity, humbleness in accepting other people’s opinions was phenomenal. “He said what thickness he wanted, the leather he wanted and how he wanted it. He was very pleased, and so was I.”

Lucio Costa admired Sergio. To him, Sergio managed to rescue the spirit of traditional furniture and aspects of indigenous Brazil. “He made the Brazilian Brazil coexist with the Ipanema Brazil.”

Sergio Bernardes had already designed armchairs creatively, armchairs that lacked the ordinary structure. Like one that had four legs, crossmembers etc., and two large rolls and a leather or canvas screen that gave it its back. “You would sit in it and could always mold it to your body. I used to say: ‘A skinny girl sitting here can settle herself in and keep her body upright. But if a heavier person sits in it, he or she will sink in and you will have a different slant on the back and the seat.’ And he said, ‘No! This is how it must be!’. I mean, he was a joker.” Arthur Lício Pontual made a couch that could be taken apart completely. The cushions were loose.

Sergio wanted to show the quality of Oca’s artisans. The “Chifruda” chair was born from the desire to show the quality of the stitching of the leather elements. “I figured that the chair would get a few playful details or details that kept a distant relationship with period furniture, in addition to a certain playful aspect, which was already my passion for the Vikings. Hence that horn – a headrest with that sharp shape. I made the chair. People found it very strange. It was very funny. But, at the time, the puritans thought it was a little strange. A lack of taste. I have nothing to do with that, right?! Whether or not they liked it was not my problem.”

Sergio says the exhibition was a big hit because it featured “important folks.” After that came other exhibits, including works of art made by well-known artists, guided by Jaime Maurício, the Correio da Manhã newspaper art critic.

While people came in to the store to enjoy the exhibits, Sergio would keep the Chifruda chair at a corner of the store to be seen, analyzed, and tested.

Always keeping pace with the effervescent changes of the 1950s and 1960s, Sergio made room for more recognition for the design profession at both exhibitions and at his store. Despite being a less known facet of his, he also wrote articles for publications such as Senhor and Módulo in this period. His pieces were filled with irony and jokes, ignited a process of awareness and created an audience of readers for the design area.

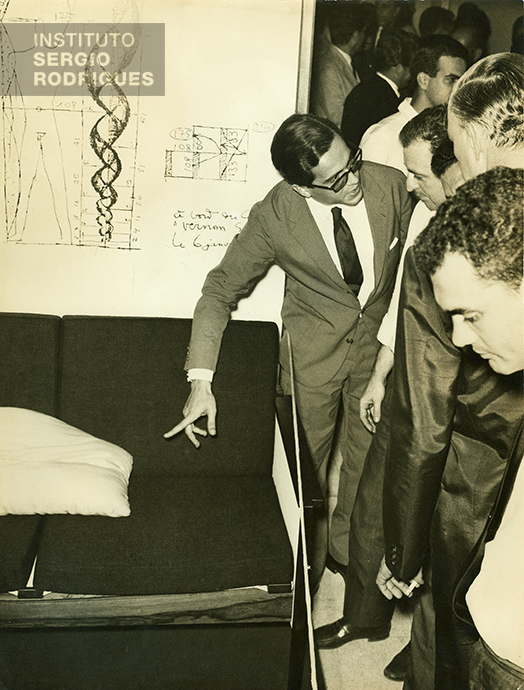

Event at the Oca store, at Rua Jangadeiros, 14 - store c, Ipanema - Rio de Janeiro, in the 1960s.

"Aspas Chifruda" armchair presented during the second Oca "Furniture as an object of art" exhibition, in 1962.

Arthur Lício Pontual, architect, presenting his sofa during the second Oca "Furniture as an object of art" exhibition, in 1962.

Sketch of the "Aspas Chifruda" armchair Sergio Rodrigues created in 1962, presented during Oca's second "Furniture as an object of art" exhibition.